One of my most formative musical experiences occurred in Fall 1991. It was 7th grade. I’d made first chair baritone in middle school band, and I was a dorky kid who wanted desperately to be cool.

At band practice one day, several people played this looping melody line that had others cheering and singing along. I had NO idea what was happening, but I knew it involved the cool kids – especially when the band director yelled at them to stop.

They played the song before and after band practice, before and after march practice, and in the stands at football games. Each time, the students got excited while the teachers got mad.

Even for a rule-following nerd like me, that tension was electric and enticing.

I put my best music skills to work learning the tune on my own. About a week later, I meekly joined in with the other players, totally surprising them. My eighth grade friend at first chair trombone asked me if I knew the song. I replied I only learned that small bit so I could feel like part of the group. He told me it was “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” by a Houston rap group called The Geto Boys. Later that week, he gave me a cassette tape with just that song.

Nothing in my experience prepared me for what I heard. Not the country and rock of my parents, less the Christian music my family played on the car radio. My virgin ears were absolutely scalded by the lyrical content, as the trio recounted dramatic, violent episodes from their lives.

I quickly threw the tape away before my parents found it. They did NOT like rap music. To be clear, neither did I. Outside of pop hits like MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This” and Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby,” I was convinced that rap and hip-hop was bad music made by bad people.

Why? Because that’s what my parents told me. It’s definitely what the news programs my parents and grandparents watched told them. Those opinions were sent into overdrive by the 1992 Rodney King riots. Nightly news shows and daytime talk programs conveyed the message that the rioters were bad people. Moreover, they got these messages from the gangsta rap that had become popular in the last few years.

Suffice to say, I was the perfect poster child for Who Got the Camera?: A History of Rap and Reality.

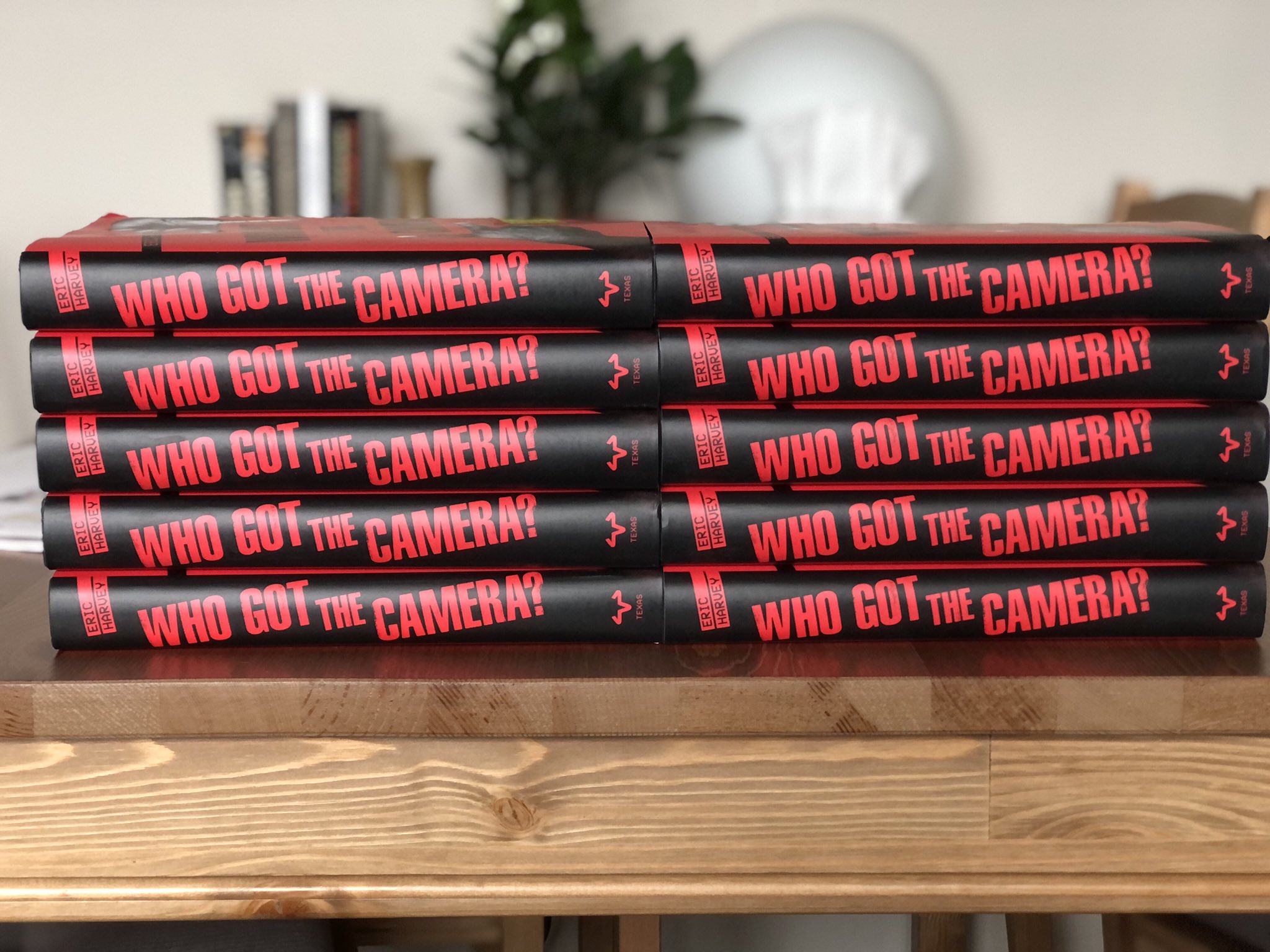

In this impressive work of media criticism, Eric Harvey compares and contrasts the concurrent rise of reality/tabloid television and reality/gangsta rap. The book is an immersive and comprehensive case study with a wide depth and breadth of research subjects. It explores the vast intersections between the prominent rappers and television personalities who dominated American popular culture in the ’90s.

Published by University of Texas Press, the book examines the rise of shows like COPS and America’s Most Wanted with their very police-first view of the world. It juxtaposes such programs against the powerful political and street-level rap that came alive in the late ’80s and ’90s. Harvey analyzes the history of artists like Public Enemy, N.W.A., Snoop Dogg, and Tupac Shakur through the lens of their music and lyrics. He investigates how their art was systematically attacked by moral entrepreneurs (a term the book uses derisively) like Tipper Gore, Geraldo Rivera, and Nick Navarro.

Harvey digs deep into how the media actively sought to demonize reality rappers.

However, the majority of the artists doubled down on their belief that they were telling the day-to-day stories of life on the streets. That proved true especially when it came to their interactions with law enforcement. To that end, Who Got the Camera? focuses intently on the growth of manufactured realness, faux authenticity, and consumer-driven sensationalism on both sides of the equation.

Copious examples showcase how the moral entrepreneurs attempted to use the rawness of the music to their advantage. By shocking and scaring television audiences, they could get the mainstream on their side in their pursuit of moral authority. The artists frequently countered such actions by standing up for themselves in interviews and media appearances. While it worked to their detriment in the early days, by the end of the ‘90s, album sales revealed that the music-buying public enjoyed the controversy.

Eric Harvey indicts the media at large for speaking from a cop-first perspective across seven strong chapters.

He accomplishes this goal by engaging in rigorous analysis of censorship, First Amendment rights, lyrical interpretation, and more. The book also disdains the copious consumerism inherent in late capitalism that spurred the drive for increased “reality” access to people’s lives. He provides a strong case that the events and cultural malaise of the 2010s (and beyond) reflect and perpetuate what the ’90s began.

I’m especially enamored with the “Conclusion” section. It lays out a convincing case that we’re currently reliving the ’90s culture wars because Americans still lack any sort of deep-seated media literacy. A curious combination of realism and immediacy is being manipulated to re-imagine and re-interpret popular discourse.

The book then holds up the Black Lives Matter movement as a positive example of how popular media can be flipped on its head and democratized. That organization and others advocate for positions and social causes that actually help people of color and marginalized communities.

In the era of streaming services and social media, it’s easy to forget that there was a time that so-called problematic art was vilified. Conservative media censored rap and hip-hop because it told stories that ran counter to what people were traditionally taught. That’s what makes Eric Harvey’s book a profound work of cultural criticism. He reveals exactly how media outlets have always sought to protect the powerful at the expense of the powerless.

Who Got the Camera? regularly points out instances where artists got too “real” in their art. It also believes that rappers should be able to write lyrics reflecting their world without people assuming their lyrics are true.