One of the best new podcasts I’ve found in 2018 in Cocaine and Rhinestones. As the son of legendary outlaw country artist David Allen Coe, Tyler Mahan Coe grew up listening to all manner of stories, myths, and legends about the people and events that comprise the history of 20th century country & western music. Yet, while he could simply recount those accounts verbatim from the depths of his memory, Coe instead chooses to invest a high level of research into each and every episode because he knows the subject matter and the listener deserves it.

From Episode 1 about Ernest Tubb, it was quickly obvious that this would be no ordinary podcast about music.

Coe is specifically interested in cracking open long-held beliefs about the foundational characters and tales of country music, not because he wants to upset any apple carts per se, but because the truth really is stranger and more captivating than fiction ever could be. And this is never more apparent than on his episode about “Okie from Muskogee” by Merle Haggard, the episode that Coe himself admits has received the most attention – both positive and negative – than anything else in Season 1.

Easily the most well-known song in Haggard’s corpus, it’s also the most misunderstood. The popular opinion states that it’s a politically conservative song released in the 1960’s that makes fun of hippie culture and lambasts their anti-war attitudes. On the other hand, a vocal minority contends that Haggard was poking fun at conservative predilections and perspectives by pointing out some inherent contradictions in the way they see the world.

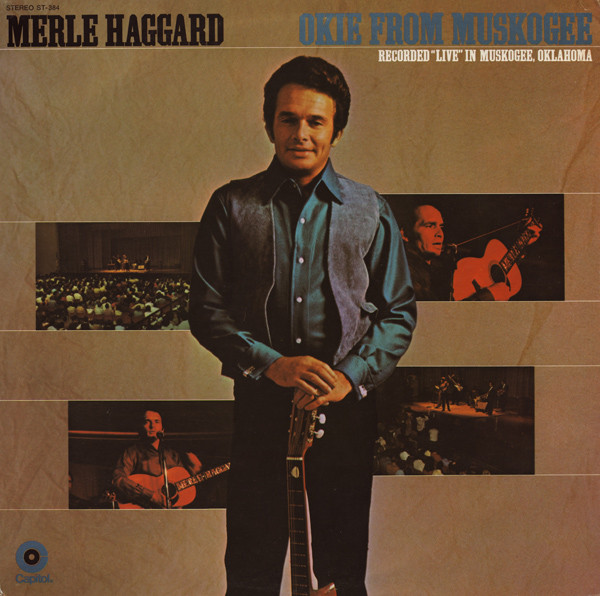

So, when Bloomsbury sent me a copy of one of the newest installments in its 33-1/3 series about the live album of the same name, I was instantly intrigued.

How would this book by Rachel Lee Rubin compare to Coe’s podcast episode? What would be her perspective on the song and album? What percentage of conflict or agreement might there be? Did the two even know about the work the other was doing? Would I finish the book and feel disappointed about the song, the artist, the writer, and/or the podcaster to any degree?

Suffice to say, I didn’t need to be worried in the slightest. “Okie from Muskogee: Recorded ‘Live’ in Muskogee, OK” serves as a master class of what the 33-1/3 series should and could be, both in terms of scholarly depth and popular interest. As Professor of American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston, Dr. Rubin proved especially adept in the sociocultural research necessary to ground a book, but she also comes across as a fan of Merle Haggard the artist. Walking that very thin line required an intense amount of skill and respect for the reader and the music, and we’re all the better for it.

The book contains five important chapters, while the sixth serves as the author’s obituary of Haggard.

Each digs deep into a fundamental aspect of this seminal artist’s life and career, which provides deeper and deeper levels of context for understanding the man, the music, and the song. Rubin’s ultimate goal: if you really want to have an informed opinion about this song, it had better go far beyond any surface-level reading rooted in your knee-jerk politics.

In “Hag as Historian,” Rubin dives headlong into the story of Merle Haggard – his work, his place in country music, the controversy around the song, the recording of this “live” album, and the origins of the word “Okie.” This introduction to the contradictions and conflict surrounding Haggard, and the titular song serves as her template for the overall thrust of her thesis – there are no pat answers, and you should get used to that fact.

With “Hag Gets Hard,” Rubin introduced us to the wild and free-wheeling world of the Bakersfield music scene.

Running intentionally and subliminally counter to the slick sounds of Nashville, this grounding helped the reader understand Hag’s personal history as the child of Dust Bowl Okies who emigrated to California during the Depression. From there, we learned how the confluence of Bakersfield, Haggard’s own history, and the greater history of Okies in California impacted the direction of the artist’s style, ethos, and career.

By the end of “Hag As Hero,” Rubin finally completed the foundation she’s been laying for three chapters. This one specifically spoke to the storytelling impulse that arose in country music during the ‘50s and ‘60s, while also contending with issues of authorial intent and authenticity. The idea was presented as follows:

- As country music arose from being a regional trend for rural audiences to a national industry consumed in both rural and urban populations, the genre had to fight misunderstandings about the culture and environment that bred most country music stars.

- Even as its profile grew, country music was still regarded as by hillbillies and for hillbillies.

- Country music fans wanted its artists to come from the same dirt-poor conditions as many of the characters in the songs they sang.

- The more authentic your own personal origin story seemed, the more authentic and “country” your music really was.

Hence, by telling tales that were sounded autobiographical, the country music listening audience found you increasingly authentic. The confusion arose when people begin to conflate the stories a singer told with that singer’s actual life and life experiences.

Which brings us to “Hag Gets Hit,” wherein Rubin effectively chronicled how the general musical public – both liberals and conservatives – greatly misunderstood “Okie from Muskogee.”

In fact, as Tyler Mahan Coe would probably agree, people to this day actively misunderstand the intent, tone, and point of the song, choosing to read their own biases into Haggard’s song. Rubin also took great strides to display how a great many of the themes Haggard sang about in “Okie from Muskogee” run in direct conflict with the values he evinced in other tunes – especially if you took them at face value because of the supposed authenticity of his work.

To his credit as both an artist and businessman, Haggard never owned up to a concrete definition of the “point” of the tune. He recognized very quickly that the song was popular with a certain audience, and he would jeopardize future record sales and concert attendance from across the spectrum if he told people what the song was really “about” when he wrote it. He preferred to give oblique answers throughout the rest of his life about “Okie from Muskogee,” even as liberals branded him a conservative hillbilly and conservatives hailed him as a patriotic hero out to (in the parlance of this decade) own the libs.

In short, what mattered to Haggard is that the people kept buying his music and attending his concerts. He wasn’t interested in scoring points for authenticity.

As the last full-length chapter, “Hag’s Two Hands” allowed Rubin to explore Haggard’s ties to labor, giving specific mention to the historically left-leaning perspectives espoused by the greater labor movement. She efficiently portrayed how Haggard self-identified with and lionized the working class, especially in how he connected the greater tenets of folk history to labor. Moreover, through cogent examples of class resentment in his own songs, Rubin provides further credence to her belief that the Haggard who sang “Okie from Muskogee” most likely didn’t agree with the politics of the song itself.

“Okie from Muskogee: Recorded ‘Live’ in Muskogee, OK” proved to be a superb and insightful book, one that rejected easy classification, much like its subject. An obvious fan of Haggard’s work, Rachel Lee Rubin matched deep scholarship with delightful storytelling and a deft touch at constructing a nearly unassailable argument. By skillfully critiquing the fifty-plus years of simplistic interpretations of “Okie from Muskogee,” Rubin could commit herself and her readers to an honest assessment of Haggard’s career and his defining contribution to country music.