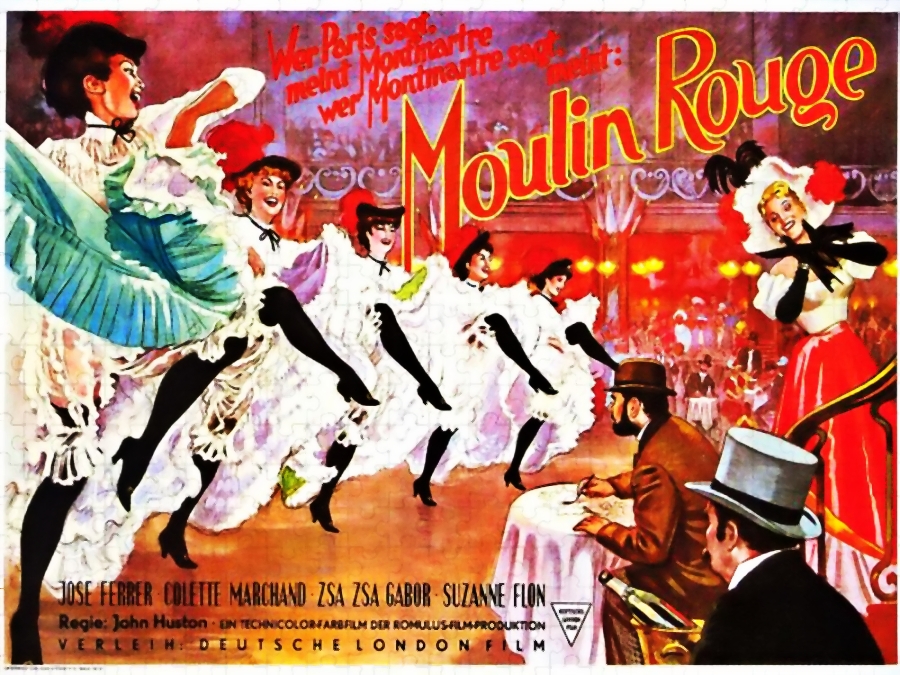

Old Academy Anew explores Moulin Rouge – 1952, this month. Based on all the reboots, reimaginings, remakes, and adaptations bombarding us lately, you might think you’ve seen something similar; yet, this film isn’t close to the 2001 vehicle with Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor— not even a little.

First, there are songs, but it’s not a musical. Second, the Academy website and Wikipedia call it a drama. It’s a freaking tragedy actually, although such movies are not considered a genre on their own.

WAS MOULIN ROUGE CONSIDERED WHAT IT TRULY IS: A BIOPIC IN THE 1950S? OR DID IT FORESHADOW WHAT WE DO TODAY, USING A FRANCHISE NAME TO LURE AUDIENCES ONLY FOR IT TO BE BARELY ADJACENT TO THE ORIGINAL SUBJECT?

Regardless of the fabled establishment being an intrinsic part of the story, the movie is not true about it. The film follows Henri, the future whatever number count of Toulouse-Lautrec (Jose Ferrer), a painter who exiled himself to Paris because he wasn’t welcomed in his own home.

ROUGE

The movie starts with a sign, telling us about dusty brushes and dried inspiration. Nevertheless, all will be restored at least for a while if we take the time to share the journey. My first cynic thought, should I know who this guy is? Because remember, I sat to watch this thinking of Kidman and McGregor. Mind you, the last time I watched the 2001 film was probably in 2010…

The infamous red windmill emerges in silence, followed by Paris, 1890. We have a place. We have time. Here we go. Well-dressed people alight from carriages, others on foot, but all with one destination. The throng enters— quietly at first, bearings changing as lively music invade their (and ours) senses.

SOON WE ARE ENVELOPED IN THE RAUCOUS ATMOSPHERE AS PEOPLE GREET, YELL, AND CHEER. DRINKS FLOW; MERRY ABOUND: MOULIN ROUGE ENCHANTS US WITH ITS MAGIC.

Two women and two men dance. Their efforts seem a concerted choreography for a moment, but quickly we realize that while the men might be in a choreographed battle, the women are truly at odds when one jeers, “I hope you split your britches, kid!”

As the tension between the women rises, we are turned to a hand sketching the scene, in what I suspect is the actual tablecloth. The dance floor battle continues, escalating to tripping and pushing. The spectators approve of these antics with catcalls and whistles, nearly drowning the band’s music. We see plenty of granny panties and ripped stockings as the women pirouette and kick. The number ends to deafening applause, and the patrons easily take over the dance floor, couples swirling and zigzagging.

The camera pans to the patrons not dancing, and we take a little peek into their stories; it is fast but quite insightful until we reach a man that at first impression is kneeling instead of sitting by his table. The owner of the sketching hand was indeed doing it directly on the tablecloth.

He gulps a full glass in one go and a woman comes behind him, admonishing, “You should not drink so fast, Monsieur Lautrec. It burns your stomach.” His simple response: “I’m thirsty. Please.” “Wine is for thirst,” insists the woman. “At least you did not say water,” retorts the bespectacled artist.

THEN MOULIN ROUGE SLINGS THE FRENCH-EST OF ALL FRENCH PHRASES WHEN THE WOMAN PRONOUNCES, “WATER IS FOR AMERICANS.”

Sold! I freaking cackled.

She still pours another glass of cognac and leaves the bottle to be inhaled by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. As she departs, the owner of the gallery where Henri shows his paintings appears with amazing news. A very famous collector stopped by the gallery and admired one of Henri’s pieces. The man is visibly excited, but Henri is impassive.

“Did he buy?” Henri asks. The gallery owner answers, “No but…” Henri offers his friend a drink but the other, a bundle of happy energy, jumps to greet someone or other and leaves. Alone again, Henri keeps sketching.

One of the women of the initial dance battle makes her around about the tables facing the dance floor. When she arrives at Henri’s, she asks if he saw the other dancer trip her. Henri gives an affirmative response but adds that he also noticed her kicking the other one’s derriere. She launches into a description of all the things she’ll do to her enemy. Her diatribe ends with, “Pull her heart out and feed it to my cat.”

As it usually happens, the future cat food is behind her and hears the whole thing. Henri eggs her, “If you can get her. She has long arms.” The dancer swears she will break those arms, and the other seizes a moment to repay the earlier butt-boot with a well-aimed kick.

Henri pours a drink for the first woman, who thanks him and throws the drink in the other’s face. Henri repeats the operation by offering the second drink to the cognac-drenched newcomer, who in turn flings the amber-colored poison at the other. “Now we are all friends again,” summarizes Henri. Nope. A cat fight ensues, hair-pulling, head-butting, and floor-rolling included.

I COULDN’T HELP BUT WONDER IF MOULIN ROUGE WAS LOW-KEY TELLING ME THAT HENRI WAS ONE OF THOSE SADISTIC ARTISTS WHO LOVES TO SEE THINGS BURN AROUND THEM.

The women are removed and the party continues. The owner of the club comes to Henri begrudging his employees’ behavior. He sees what Henri has been sketching and agrees that it’s not bad; it could even become a poster to advertise the Moulin. He offers Henri a month of free drinks for the completion of the poster. Do we even need to wonder if Henri accepts?

We realize there is silence. Out of nowhere and surely for no other particular reason than to make her do something Zsa Zsa Gabor shows up to sing. The song, so slow and so conflicting with everything we’ve seen until that moment, is absolutely jarring. She sings about falling in love in May. Here I am hoping the song will pick up the pace at some point; we aren’t in a freaking theater but the EFFING MOULIN ROUGE. Honestly, I don’t think the song is longer than three minutes, but it feels like thirty.

DUDE, 1952’S MOULIN ROUGE IS NOT A MUSICAL— DON’T FREAKING FORCE IT.

Zsa Zsa ends her horrible song sitting by Henri; people enthusiastically applaud, but I’m not buying it. She and Henri talk, and we learn that she falls in love a lot, like a lot, lot. The songstress dramatizes and commiserates about her (every other week) broken heart only to turn her gaze and find a handsome man in military regalia. She exclaims, “There is the most beautiful creature. Look at those shoulders.” And I think, “Look at those legs.” But Henri says, “For your sake, I pray they are not padded.” Pretty sure, Henri ain’t talkin’ ’bout shoulders.

ROGUE

The Can-Can dancers finally show up, and we enjoy the famous song and dance. This is the closing act of the night. The patrons depart sated after a night of debauchery. Henri is the last to leave the place. Here is where we learn what Mistress Gabor meant when she dreamily asked him, “Oh Henri, why couldn’t you be tall and handsome?” when they sat together earlier. Henri is a (very impolitically correct nowadays) comically short man.

With the help of his cane, Henri limps home amid the almost but not completely deserted streets of Paris. A reveler, from a group leaving a nightclub, makes fun of him. The jerk states it’s good luck to rub hunchbacks and midgets on the back. His words, not mine. Henri threatens to hit him with his cane but decides the man is not worth his effort. Never fear. We’ll see other uses for the cane in the third act.

THERE’S A HEARTBREAKING SADNESS ABOUT HENRI, AND MOULIN ROUGE MAKES ME THINK OF DEMENTORS.

The score accompanying this limping journey is full of tragic strings, reinforcing our hero’s desolation. Movie gotta movie, though. So we get a flashback, serving us Henri’s back story. Since I want you to watch this film, I’m just gonna say, shorty is a blue blood and people should not marry their blood relations. The flashback lasts barely five minutes, and even if they feel longer it’s in a completely different way from that atrocious slow song I’m not gonna stop bitching about because the third act will feature an even worse one.

The flashback ends, and we return to the dark, cobbled streets. Suddenly, a woman appears behind Henri in fear of being attacked. She grabs Henri’s arm and begs him to say they’re together. Tall and pretty, we get a clue by the hour and place that she’s a working lady. He agrees, and they walk together for a few minutes until a man yanks her away from him. The man is a police sergeant. We never really learn what she did to be chased around, but Henri defends her. They have been together all night, and they saw a woman running the other way. The sergeant recognizes Henri and lets the matter die.

After a couple of blocks, Henri tries to get rid of this impromptu friend. She refuses, giving excuses implausible (but somehow congruent with her station). They end up at Henri’s. She’s pretty but rough around the edges. If this were a movie set today, I’d describe her behavior as a junkie about to start jonesing for a fix. That’s the way she’s portrayed as long as she is around Henri, which is a while because Marie Charlet (Colette Marchand) not only stays for that night but they become lovers.

THEIR RELATIONSHIP IS TOXIC, CHAOTIC, AND FULL OF RESENTMENT. MOULIN ROUGE TURNS INTO A TREATY ABOUT HEAVILY DYSFUNCTIONAL CODEPENDENCY. AND IT’S FREAKING SCARY.

Their performance as a toxic couple is so spectacularly real, that you absolutely want to strangle both and throw them in the Seine afterward. Alas, great art comes from the abyss, and her sulfurous fumes push him to create the piece that makes Henri truly famous.

ROUGH

The first moments of the film lure you in with song and dance, but once the tragedy takes hold of you— it is inescapable. Still, this is a masterpiece of cinema. The tragedy and desolation of being different, largely by the sins of your ancestors, is a cross Henri bears with effort. Not with aplomb but with a pathetic stoicism that breaks you. As a viewer, you feel like an intruder, forcing yourself into the life of this sad human being. Yes, he was a genius, and, unlike other great painters of the time, was recognized as such while still alive.

Yet, if you’re a person capable of some introspection you can see a little bit of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec inside you now and then. Whenever something doesn’t come to fruition and you feel that it’s your fault but at the same time you’re aware that you never truly had control over it whatsoever. Seeing Henri being cruel, teaches us about our own moments of cruelty. How our resentments are really just us lashing out at our inability to thwart the destiny others traced for us because, in the end, we complied.

MOULIN ROUGE SURPRISED ME IN UNEXPECTED WAYS. JOSE FERRER PLAYING BOTH RECALCITRANT FATHER AND BROKEN SON IS A STROKE OF SUBVERSION YOU ONLY GET AFTER MARINATING ON THE FILM FOR A WHILE.

The third act is the best act of the movie. Not because there is a resolution but because the story takes an unsuspected turn, giving us more, tricking us into believing that a happy ending is possible for Henri. Nothing further from the truth, but we take it gladly because we want to follow this dark almost empty road till the end.

Interestingly, there is an actual French biopic entitled simply Lautrec (1998) in case you’re interested in a more reliable portrait of this master of Postimpressionism.

I’m giving Moulin Rouge 9 out of 10 because Zsa Zsa Gabor could have been in the movie without singing and Jose Ferrer floating like a Muppet whenever he walked was somewhat distracting.

Moulin Rogue is available on VUDU.