The first time I ever heard a Moog or analog synthesizer was in 1997, courtesy of Joy Electric. Even in the niche genre that is Contemporary Christian Music, Ronnie Martin set himself even farther on the fringes by composing goth-pop songs about Jesus on a monophonic synth incapable of playing a traditional chord.

I was completely enamored by this method of music-making. It struck me as the right sort of outside art – Joy Electric didn’t use such an instrument to make some sort of twee curio statement. He did it because he liked it and was good at it.

I spent several years working in Christian retail trying to convert people to the Gospel of Joy Electric. My former coworkers might even attribute my tepid career as a music writer to convincing customers that they really did should add this combination of twinkling synths, breathy falsetto tenor, and fantastical lyrics to their collection of Jesus music.

Despite my fascination with the Moog, I wasn’t exposed to Switched-on Bach until my late 20’s. I was playing Joy Electric late one evening at the coffee shop where I worked, and one of my favorite customers stopped short as soon as they entered the store. After absorbing the music for a few moments, they walked over to me and asked,

“Is that a Moog I hear in that music?”

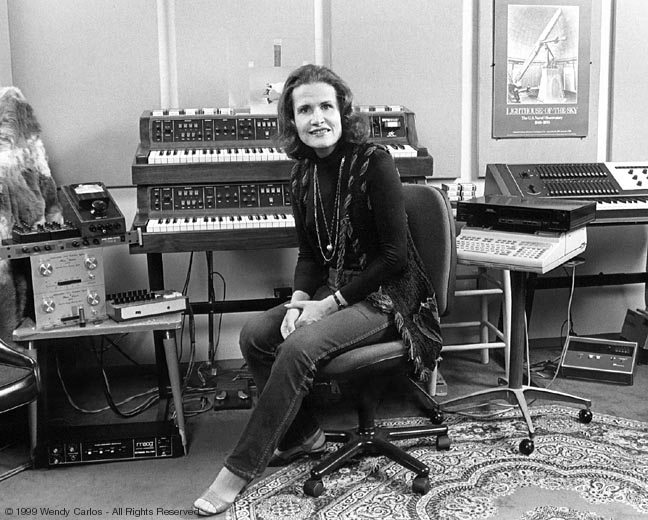

I quickly responded in the affirmative and proceeded to gush about Joy Electric. Being a professional composer in their own right, they immediately started quizzing me on the music of Wendy Carlos. The name wasn’t familiar to me, but the music was – especially the classic TRON soundtrack, a movie I watched dozens of times as a kid. This beloved customer promised to bring me THE Wendy Carlos album on their next visit, and once I had a burned CD of Switched-On Bach in my hands, it didn’t leave my car’s CD player for a week.

So, when I learned that Bloomsbury was releasing a new 33 1/3 installment about this excellent collection of Johann Sebastian Bach songs performed on a Moog, I was eager to read and review it. But I was not expecting to be alternately dazzled and challenged by Roshanak Kheshti’s critical examination of culture, technology, and journalism. She examines feminism, gender, class, and sexuality through the lens of people’s fear of change as represented by the album, the Moog, and Wendy Carlos.

Upon my first read-through, I was confused by the lack of information and insight into the music itself, these 250-year-old acclaimed compositions. I wondered openly as to why Kheshti failed to provide any backstory of the songs – even bits about why Carlos chose what to record what she did. But as I started to read the book again, the realization hit: the music is actually immaterial to why the album is important. The timelessness of Bach’s music may have helped convince the greater public to purchase the album – which won multiple Grammy Awards and gone multi-platinum – but the true story lies in the person of Wendy Carlos and the Moog as a way to make music.

The book asks you to assume the music to be self-evident: Carlos played Bach songs on a Moog. That’s that. What’s actually worth discussing is the context of the music, not the content. Hence, the book is best understood as a deep dive into the life of Carlos, the Moog as an instrument, and how together they helped create, shape, and change the popular discourse on how music performed solely on a synthesizer should be regarded.

Thus, understanding the hows, whens, and whys driving Carlos, her aesthetic, and the response to them proved much more interesting and worthy of reflection. Early and often, Kheshti drives home the point that the synthesizer is a valid form of music-making, one that was championed primarily by women from its earliest days. Making music this way continues to be revolutionary because the greater public still fetishizes traditional instrumentation.

As the argument still goes in some circles, “Electronic artists can’t be real musicians because they can’t actually play the instruments they’re voicing through a patch, mod, pad, or designed sound. Yes, such devices have keys and resemble a piano, but they aren’t really pianos, and all you’re doing is manipulating electronics with switches, cords, wires, and software.”

The case being presented in this book is that the purpose of Switched-On Bach as an album was to dispel those rumors and misunderstandings while also serving as a showcase for the Moog’s abilities and Carlos’ talents. Each note of those classic Bach compositions was carefully reproduced on the Moog by Carlos and then shaped into a lustrous whole by Carlos and her most excellent producer, Rachel Elkind. The result is an album that helped people gain a greater understanding of the role that new technology should and can take in modern music-making.

But Kheshti didn’t stop there. She dives headlong into a feminist critique of the music industry’s response to the person of Wendy Carlos and what she represented as a champion of the Moog and synths in general. By using postcolonial theory and gender studies as crucial lenses, the concept of “shape-shifting” comes to the fore. Through copious clips of Carlos interviews, the reader is introduced to the idea that sythns can represent a new expression of humanity, one that breaks down the walls of both the gender binary and technological nationalism.

To whit, early synthesizers – including the theremin – were developed as weapons, not musical instruments. Both the Soviet and American governments of the Cold War-era treated synths as a way to create agitprop, not music. Even today, the popular conceptions of technology are dominated by bros, ranging from Edison, Gates, Jobs, and Musk to gamers and characters in Silicon Valley, both real life and on HBO.

But such ideas are media creations the focus solely on straightforward functions that can be exploited for capitalistic gains. Wendy Carlos represents the idea that technology, as represented by the synthesizer, is designed to push the limits of human expression. It’s about making, not selling; it’s about exploring, not marketing; it’s about being the person you really are, not rigidly fitting everyone inside a box. In fact, Carlos gave herself the moniker of “Original Synth” and often referred to herself as a cyborg, not in the Star Trek sense, but as someone who willingly uses technology and cybernetics to push humanity into its future.

Ultimately, Khesti’s thesis rings true in my ears: the power and lasting impact of Switched-On Bach lies not the music, but in the barriers, bars, and walls it exposed. As a trans woman, Wendy Carlos spent years being interviewed about her transition and gender identity at the expense of actually talking about her music. This continues today as a woman and gender non-conforming composers are still seen as nonstandard or atypical, even as historians like Tara Rodgers have revealed the long and important history of their contributions to electronic music.

Wendy Carlos’s Switched-On Bach is the type of entry that keeps me coming back to the 33 1/3 series. Khesti’s work has completely opened up my mind and understanding of what the Moog should be as a musical instrument and what Wendy Carlos hoped to accomplish by recording music as she did. By facing detractors and naysayers head-on with her ideals and accomplishments, she pushed the shape-shifting potential of the synthesizer out of the shadows and into the forefront of musical conversation.