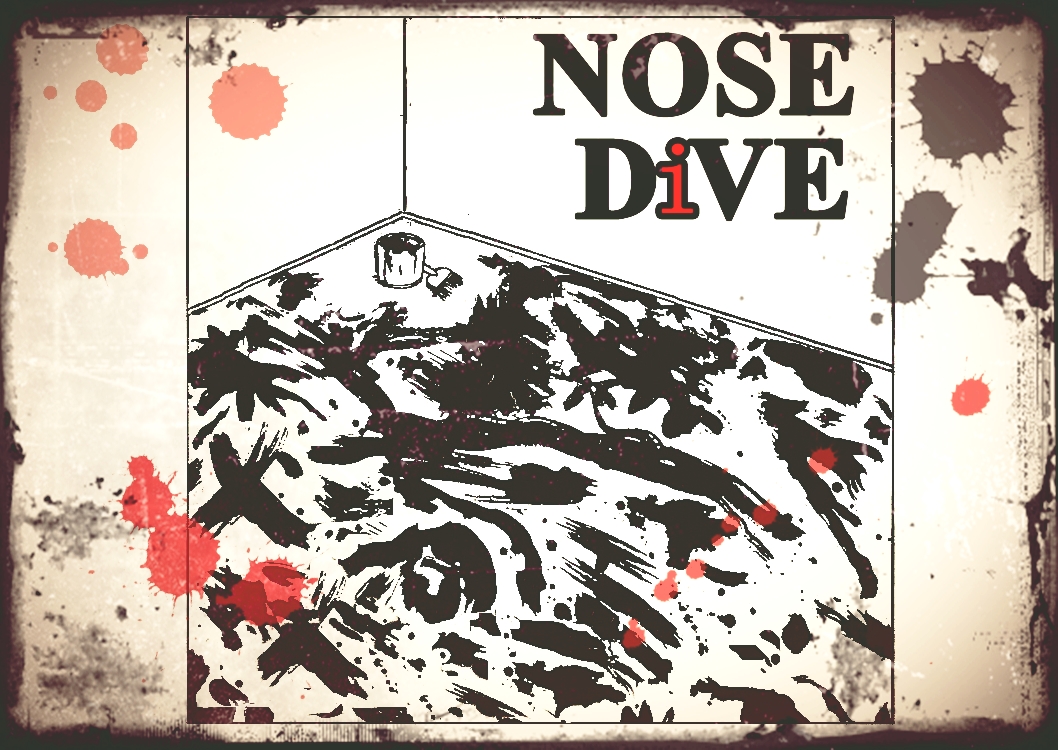

Illustration Credit: Aaron Cooper

Note from the informational ether: “Nosedive” is a collection of essays and narrative prose written by Ben Lee over the course of a year prior to his death. Per his will, I am posting these on his behalf with no changes made to his original text. He’s not that Ben Lee. He’s also fictional.

Part 1: Is Suicide Punk?

Chapter 11

The best feeling in the world is when the bottom falls out. It’s peace. It’s reincarnation. It’s emotional invincibility. All the bad things that could happen have already occurred, and all the thoughts that usually bludgeon the mind calm into serenity known only to those of us hitting bottom and Buddhist monks meditating, inflamed. For that moment, I concentrated on the concrete.

A mask pumped air into my storm clouded lungs.

Beeps rose like sleeping breaths from a tangle of machines.

Doctors came into the room and talked at me, and when they were done talking, they let me leave. All I had to show for my failed attempt at death were two lungs weak from poison, a hospital bill, the number of a psychiatrist and a marriage falling apart. One would think something more would come from this, and it kind of pisses me off thinking about it now.

Listen, I tried to kill myself three times, and three times, they let me leave the hospital with no punishment above my self-mutilation. And if not punishment, where were the people trying to save me? In movies and books and television, when people try to kill themselves, they spend some time making friends with other fucked up people in some mental ward somewhere. They learn life lessons and learn to love themselves, and even if they don’t get all the way better, the audience leaves the movie or puts down the book or turns off the television with this satisfied feeling that the hero will mostly find themselves okay.

I wasn’t looking for a faceless government to strip me of my rights and lock me away from sight in some psycho bin, but it’s scary to think someone like me could walk free without being held for at least a full psychiatric evaluation. Sure, I only hurt myself each time I tried to die, but maybe next time I’d be a danger to others as well. After three attempts, I could have gotten desperate and enacted an attempt so fucked up that I’d take other people with me.

What a doctor said on the way out of the hospital room was, “It’ll get better.”

And I said, “What the fuck are you talking about?”

“The further you get away from your son’s death, it’ll get better. An unfortunate part of my job is watching people go through grief. The further you get away from it, the more you can think of the good times. It’ll still hurt, but it’ll be better. You can be happy again.”

The bottom rose back up quicker than I expected. After my respite of inner peace, hearing some dickweed talk about my son made things matter a little more because my son mattered, and my surviving son mattered. So everything kind of mattered. My refuge from feeling was as short lived as it was beautiful, a fireworks show on a bankrupt budget.

“Shut the fuck up,” I sneered.

Biscuit met me in the waiting room, which was all I needed to know about my marriage. Simultaneously, we shrugged, and I couldn’t help myself but think that it must have looked kind of cool and choreographed like when the heroes slow walk towards the fourth wall in an action movie.

Familiar suitcases that once haunted my bedroom closet at home now haunted the wrapper littered backseat of my friend’s shitty car, no longer merely containers to transport clothes, they became demons bound to my soul. Wherever I went, at least one of these bags would follow. Whatever I planned, these bags would constitute a part of that plan. And when someone else planned my life for me, like Allison planning for me to stay with Biscuit, still those suitcases followed.

We slipped into our car seats without mentioning the bags.

“What should I say?” Biscuit asked.

“How is Damian?” I replied.

“I don’t know, man. I didn’t ask or anything. It would have been pretty fucked up if died, you know? I mean for your kid.”

“He did say it was okay.”

“Wait,” Biscuit snorted. “you asked him if it was okay if you killed yourself?”

“Yeah, well, sorta. I asked if he’d miss me if I were gone.”

He sighed but did ask, “And what did he say?”

“He said, ‘I love Mommy.’”

“That was his entire response?”

“Yeah,” I actually chuckled. “Preschoolers.”

“Allison told Amanda you can do whatever you want,” Biscuit said, glaring at a traffic light while the sun’s glare made its best attempt at obscuring our view. “Let me think. Amanda said Allison said, ‘He’s not my concern anymore. If he wants to kill himself, he can do it.’ And, um, that’s mostly it.”

“That’s it?”

“Well, that and she’s divorcing you, but I figured you already assumed that. Amanda said she said, ‘I give up.’ So there’s that, man.”

“You said Amanda said Allison said. I can’t wait to tell someone all these things Allison said so they can say, ‘Ben said Biscuit said Amanda said Allison said.’”

“Right,” Biscuit forced a laugh. “Life is fucking stupid.”

That could have been the slogan to promote my life. Life is fucking stupid. None of it makes any sense. None of it is good. We have choices as to how to approach life, but they boil down to these:

- Die as soon as possible.

- Pretend life isn’t so bad.

- Revel in life’s weirdness, accepting and absorbing the surrealness that it is wilder than any speculative fiction could ever be.

Fiction in general has to follow a structure. It has to make sense or people scream about plot holes or machines of god or just how stupid it is that someone did some nonsensical thing or whatever. So even fiction with ghosts and time machines have to stick to an internal logic the reader will believe.

Reality doesn’t have to follow any such structure. Memory doesn’t have to fill in all the holes or even be correct. People don’t have to be any one thing. They can contradict themselves in arguments, facts and personality. None of it needs to make sense, and that means all of it is weirder than any weird fiction one might read.

- Try to do enough good things to offset how terrible the world, and living in general, is.

I made my choice, obviously. As I’ve said, I will eventually have nothing more to write, and when that time comes, I will kill myself. And I’ll do it for real this time. I doubled down on my choice sinking into an untraceable scent on Biscuit’s couch in his dull apartment, rubbing the Xs on my hands and wishing they were over my eyes, wishing I hadn’t ever failed this time or last time or the first time.

It’s punk to crash on the couch or floor or spare room in a friend’s apartment, but even more punk to do so while on tour. It’s punk to clean the apartment a little and maybe cook a little as a repayment for the favor. This was more punk when I was twenty than it was in my thirties. Let’s face it, though, there wasn’t much punk left in me anymore.

My work stopped calling after a few weeks. Allison never called. Amanda sometimes came over and asked how things were, and I’d say it was fine and walk the streets with one good leg and one foot a glorified pogo stick.

Where Biscuit lived, there wasn’t much around. This place was in that weird in between that wasn’t quite suburbs and wasn’t quite country. It wasn’t really anything, and so no sidewalks showed me where I wanted to go. No sidewalks existed at all.

I’d come back and they’d be watching something on the television or fucking in the other room. Or one time, Amanda caught her own tears in her hands while Biscuit awkwardly held his hand on her shoulder. I avoided looking directly at them and crept into the guest room, certain I had tiptoed past a breakup in progress.

Later, Biscuit shook me awake and sat on my bed like a drunk deadbeat parent telling his kid he’s about to split and maybe, perhaps, did the kid have any cash he could borrow. But it wasn’t that. And it wasn’t a breakup. It was something else entirely.

“Your grandmother-in-law is dead,” Biscuit whispered.

“Okay,” I said.

“We’re going to her house tomorrow to help clean. Like, you and me, I mean. Not Amanda and me. Well, Amanda will be there too, but it’ll mostly be you and me. Not Allison, though.”

“Fine. How’d it happen?”

“I don’t know. She’s fucking old. She’s a grandma.”

Later, while we were finalizing the divorce, I made it clear to Allison and our lawyers that I didn’t want any part of the great sum of money Allison’s grandmother left her. And I didn’t want anything from Allison either. From her family, I got something else, and I’m not even counting my repaired nose or child or years of happiness or any material shit I picked up along the way.

We spent several days in each room, marking items and cardboard boxes with various color-coded stickers. A red sticker meant we’d donate. A black sticker meant we’d sell. A blue sticker meant the family would get together and rip at each other’s throats over who would get such an item. We’d throw garbage into large garbage cans lined with thick black bags, but there wasn’t much of that here. She was too rich for there to be much junk.

First, we tackled the living room and then the den and then the kitchen and then the downstairs bathroom and then the library and then the dining room and then each of the guest rooms and guest bathrooms and then the main bath and lastly (not counting the attic and the basement, which would take a week a piece), we arrived in the grandmother’s master bedroom.

Biscuit started working on the dresser and the vanity and bed stands while I took the walk-in closet that was nearly a room to itself. The clothes were easy to pack away as we had wardrobe bags where we could place each article of clothing flat with the hanger sticking out of the top like a worm poking out of the soil, and once that bag was full, we’d zip it up, hang it up and move on to the next.

But she had boxes upon boxes of tokens and knickknacks and all the junk unseen in the rest of the house, even in the designated storage areas. Only here in her bedroom closet did she keep the badges of her long, strange life. Loose photographs that never made it into albums. Loose jewelry broken or a single earing missing its twin or both. Loose charms. Tickets bound together with string or rubber bands. Toys. Watches. Lapel pins. Brooches. All sorts of tchotchkes. Music boxes. Pocket squares. Several boxes with guns and several boxes of bullets, which made me laugh, of course. I set one handgun aside and hoped I could sneak it out for myself but forgot to try.

Strangest of all were the boxes upon boxes of leather bound journals, each one corresponding to almost every year the woman was alive. And while journaling is not strange, especially for a woman of her age and time, one journal in particular caught my eye. All the others had the corresponding year visible through a hole in the cover that showed what would be the title page in any published work. This one had such a hole but nothing written on the page underneath.

I flipped through the book and found some things one would expect: names, dates, places, descriptions of events; some mundanity. However, I also found many things I did not expect, and I slinked out of the closet into the main room. Biscuit cursed into a drawer like he was farting into a jar.

“I think she’s a murderer,” I announced.

“Who?”

“Allison’s grandma. Who else?”

“Well,” Biscuit looked up. “Shit.”

We sat on her bed and thumbed through the journal. Each one of the tokens in their coffin boxes began to make sense. These were souvenirs. These were keepsakes of lives no longer, all of them the grandmother loving described in this book.

I made a decision regarding how I would spend the rest of my life. This journal would be my guide and my remaining hit points until I’d die. All the people and places within that book, I would visit, and I would write my own chapters along the way. I’d write about how I got where I was. I would write stupid fucking opinions about something as pointless and important as punk or life or whatever. And I’d write about what I discovered.

Eventually, I’d run out of places to visit. I’d run out of hit points. I’d run out of writing days.

When I have nothing left to write, I’m going to kill myself. That’s just how it’s going to be. This, I decided sitting on a bed with Biscuit in my grandmother-in-law’s bedroom – that murderous psychopath.