When The Doors were booked to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show, on September 17th, 1967, it was destined to be fire. After all, the family variety show was monumental for the careers of Elvis Presley and The Beatles. But no one ever imagined the performance would be the epitome of punk rock ethos. 15 minutes before showtime, producers asked Jim Morrison, frontman of The Doors, to change a lyric in “Light My Fire”. Girl, we couldn’t get much higher, clearly referenced drugs, and it wasn’t suitable for prime time. Morrison agreed but sang it anyway during the broadcast and just like that The Doors were banned from ever appearing on the show again. But counter-culture was in America’s living room.

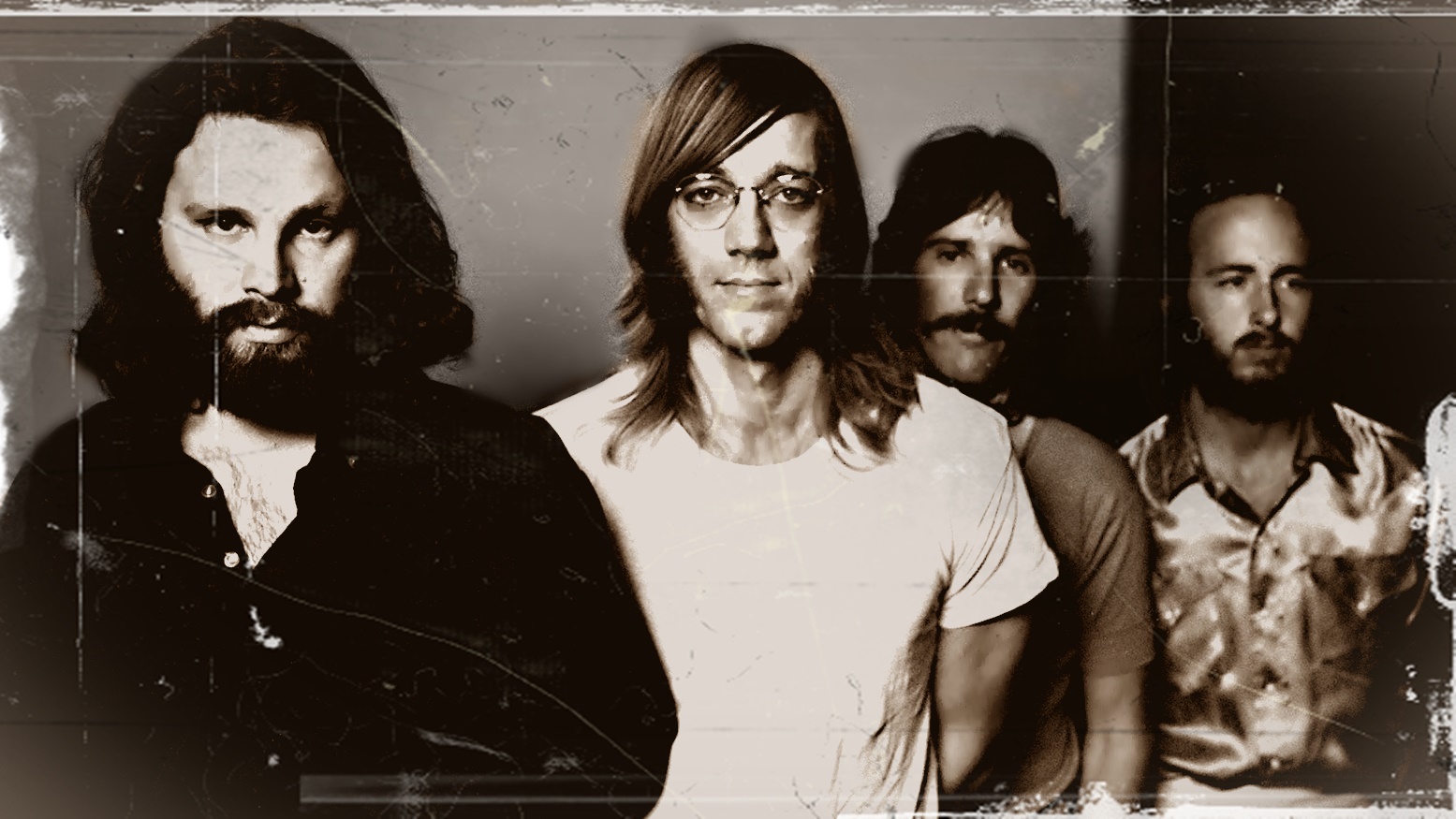

Of course, The Doors weren’t the first band to push the envelope on live television and definitely not the first to upset TV producers. But there was something about the performance that was just cooler than going against censorship. Morrison was dark, mysterious, and alluring but above all, he was honest. If the lyrics offended the old folks, then so be it! This love affair of rock n’ roll and honesty is what set The Doors apart from many acts of the time and it speaks volumes about their longevity.

One of the most remarkable aspects of The Doors and Morrison, in particular, was his unflinching perception of society.

Where most free thinkers and youngsters saw the free love movement as something beautiful, Morrison understood it wasn’t without darkness. Peace and flowers were nice, but the late 1960s were dangerous times. With so much civil unrest, segregation, and underlying sexism, it was naive to think society could just hug it out as the hippies suggested. It put Morrison in an interesting position. In some ways, The Doors felt like anti-heroes when compared to other American groups like The Beach Boys or Paul Revere & The Raiders.

Despite aesthetics firmly rooted in hedonism, The Doors weren’t all about edginess. They had countless hits on mainstream radio such as “Break On Through”, “Love Her Madly”, “Hello I Love You”, and the aforementioned “Light My Fire” among others. As one of the biggest acts of the latter part of the decade, The Doors had quite the audience. All the more reason why their final album with Morrison, L.A. Woman (coupled with Morrison’s untimely death a few months after it’s release) just felt like the end of an era.

By the time L.A. Woman dropped in 1971, America’s honeymoon was over. Old Glory had lost its innocence and counter culture was the new pop culture.

Looking back at pre-Vietnam war America, the city of Los Angeles could be seen as this mystical place where fantasies became reality. Every kid thought about moving to L.A. to get into movies and live out their wildest dreams among the Hollywood elite. Not many people achieved that goal but it didn’t stop them from fantasizing. In a lot of ways, the pursuit of an unobtainable dream was the hope a generation needed to stay focused during times of uncertainty. Unfortunately, the proverbial American Dream was just that: a fallacy. When you’re far more concerned with being drafted into the Vietnam war than walking the red carpet of a premier, you’ve officially grown up.

The opening of L.A.Woman‘s title track is the melody of “America (My Country ‘Tis Of Thee)” but perverted through a distorted piano representing the death of a dream. It was obvious The Doors were about to touch upon something listeners hadn’t really put into perspective yet. Officially kicking off “L.A. Woman” is the sound of a car speeding down the highway, setting up the symbolism Morrison was known for.

Despite being directly on the nose, the listener is well aware “L.A. Woman” will be a journey of sorts.

After the ominous piano riff and muscle car sound effects, “L.A. Woman” slowly comes alive with non-stop quarter A notes on the piano in perfect tandem with hi-hats on the drums. Bass guitar falls in the pocket along with a jazz-esque electric guitar descending the A major scale. Without getting into a lecture about music theory, “L.A. Woman” is pretty simple by design. Arguably the simplest rock song to ever grace the charts. But Morrison’s opening line (often misheard as) I did a little downer about an hour ago…. took a look around to see which way the wind blows adds more than enough attitude to elevate it beyond notes and scales. Just like the Hollywood facade, nothing is what it seems.

In music, Major scales are generally happy while Minor scales are more dramatic or sad. Even if you don’t know the first thing about music, your ears do. The color of sound often plays a vital role in what the human ear finds pleasing. No matter what, people know what happy and sad sounds like. “L.A. Woman” mainly sticks around a single note in the Major scale. It only leaves the note on a few occasions (more on that later).

With the bass riding the A note along with the driving beat, the “L.A.Woman” motif is about moving forward.

While hanging around in a single chord, “L.A.Woman” gives keyboardist Ray Manzarek, a nice landscape to explore. Most of his melodies in the song begin on a C# and often fall into Pentatonic territory. Traditionally regarded as the blues scale, the Pentatonic scale is one of the most important modes in music theory despite its simplicity. Being there are no dissonant intervals between any of the notes in the scale, they sound good in any order. This explains why improvisation is always associated with Rock and Blues. Musicians can spend more time playing what they feel instead of thinking of the proper note to stop or start on.

But The Doors one-up that notion and do all these Pentatonic guitar and piano fills over a Major scale. The contrast makes the rhythm section far more upbeat than it really is, while the improvised leads feel more dramatic or soulful. The melodies are literally manipulating how you feel about what you’re hearing.

Manipulation for the sake of melody enhancement doesn’t stop with instrumentation. Morrison’s thematic duality is front and center with his lyrics.

To fully appreciate Morrison’s impressionism, you have to understand his love for French Symbolists. After all, we’re so caught up in labeling Morrison as a rock star, that we forget his love of poetry. A single line of dialog could have multiple meanings depending on how far one wishes to theorize. Lyrically speaking, “L.A. Woman” is very surface but going back to the line in “Light My Fire”, we already know Morrison was far more complex than mere hooks. Looking at the lyrics from a symbolic standpoint reveals Morrison’s true sentiments of city and era.

Well, I just got into town about an hour ago

Took a look around, see which way the wind blows

Where the little girls in their Hollywood bungalows

Are you a lucky little lady in the City of Light

Or just another lost angel?

City of Night, City of Night

L.A. woman, Sunday afternoon

Drive through your suburbs

Into your blues, into your blues,

At face value, these lyrics aren’t very intricate. It could very well be about a particular woman the protagonist is flirting with. Or it could be a metaphor for Los Angeles itself.

However, the music does something interesting during the lines City of Night and Into your blues. For the first time in the composition, there’s a chord change. At the end of each line of the chorus, the chord drops from A to G. So while we’re led to believe “L.A. Woman” would be a traditional blues jam by way of the Pentatonic guitar and keys, it’s actually closer to the Lydian scale.

The best way to describe the Lydian scale is dreaminess. Moving a major chord a whole step down to another major chord and back is dramatic but not abrupt in the slightest. The change adds color without changing the landscape. This fits in with the thematics Morrison offers in “L.A. Woman”. Is this a song about the beauty of the entertainment world’s most important city, or a bleak cautionary tale? The more you think about the composition and lyrics, the more you realize there are more questions than answers.

Things take yet another dramatic turn with the following lyric:

Motel, money, murder, madness

Let’s change the mood from glad to sadness

The canonical meaning of this line has been debated for years. Motel, money, murder, madness may be about the mysterious death of R&B singer-songwriter Sam Cooke. In late 1964, Cooke was shot and killed by the manager of the Hacienda Hotel in a seedy part of Los Angeles. While the courts ruled it justifiable homicide, the Cooke estate believes it was conspiracy and murder. Regardless of how you may feel, it’s a story of mysterious intrigue rarely discussed in the early part of the decade.

Living the bohemian lifestyle, Morrison was no stranger to cheap hotels. Where most of Hollywood’s elite partied in places like the Playboy Mansion, Morrison often chilled in the smaller, grittier clubs and dives found in the underbelly of the city. He probably stayed at the Hacienda Hotel quite a few times and heard many variations and theories on Cooke’s death. There were cracks in Hollywood’s foundations and Morrison was there to revel in it.

Let’s change the mood from glad to sadness could also be seen as a direct reference to the tragedy that essentially killed the summer of love: The Manson Family Murders.

The murders of Sharon Tate, Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, and Wojciech Frykowski on August 9th, 1969 changed everything in Hollywood. Actors, actresses, rock stars, and filmmakers who once partied together every night of the week were now locking all doors and sleeping with loaded weapons. Outside of Los Angeles, society’s perception of peace-loving hippies changed to dangerous, bloodthirsty killers.

Morrison was a long-time friend of Jay Sebring. Not only was he responsible for Morrison’s free-flowing style, but he was also a close friend. The line Let’s change the mood from glad to sadness has far more personal weight than we probably give credit for. The Manson Family member responsible for the murders was Tex Watson. It’s also worth noting, that Watson briefly worked as a doorman at The Whiskey A-Go-Go, the same club where The Doors had been a house band. It’s not a stretch to assume Morrison had at least once occupied the same place of employment with the person who would later murder a friend and change the world.

Perhaps the murders were just a little too close to home for Morrison and the dual nature of “L.A.Woman” reflects that?

Maybe Morrison had enough of the city where he spent most of his life. Growing tired of the scene and selling out arenas, he moved to Paris not long after L.A.Woman was released. Morrison’s close friends claim he wanted to unwind and spend time with his girlfriend who moved there a few months before. Showcasing the city’s iconic scenery and seedy underbelly in “L.A. Woman” is almost like a bittersweet goodbye to a life Morrison was ready to take a break from.

Even if the notion is a bit of a reach, it’s safe to say Los Angeles was no longer a scene of peace and love by the time 1971 rolled around. The glitz and glamor were replaced by fear and paranoia. The Doors had always made subtle references to the darker side of human nature but seeing happen around you was a different story. For every sun-soaked breeze on the strip, there’s a low-rent strip club. For each bikini-clad girl on the beach, there’s an ominous figure lurking in the shadows. Throughout his short, yet prolific career, Morrison lived by this unspoken code of honesty centering his artistic output around death and beauty for better or worse. Both sides of the coin are prominent throughout “L.A.Woman” just as they are in waking life.