Let’s get this out of the way at the jump – dc Talk is one of the foundational bands in my personal music canon.

Once I started showing interest in music outside of the ‘80s country my Dad enjoyed and the children’s songs the family played on car rides, my parents quickly plugged me into the world of Contemporary Christian Music (CCM).

Out of safety for my ears, they were more concerned with the lyrical content of the music I listened to than the actual genre. Lo and behold, once I learned about the types of CCM acts making music even remotely akin to the stuff my friends in middle school liked, it was easy to get my parents to approve the albums I bought with my lawn mowing and babysitting money.

After a few mild dalliances with the likes of Carman, Steven Curtis Chapman, and Michael W. Smith, I quickly latched onto two acts: Petra and dc Talk. Petra was played all the time in my house and car (at least when Dad wasn’t around) because it was driving rock music of the sort my Mom loved, and the over-the-top Christian lyrics definitely helped.

But dc Talk was different, as neither of my parents showed any affinity for hip-hop in the slightest. Thankfully, after reading the liner notes for Nu Thang and Free at Last, my Mom was convinced that the group was Christian, even if she didn’t like the music.

In fact, I listened to Free at Last so much between its release in 1992 and its eventual usurpation by Jesus Freak in 1995, that I completely wore out two different cassettes.

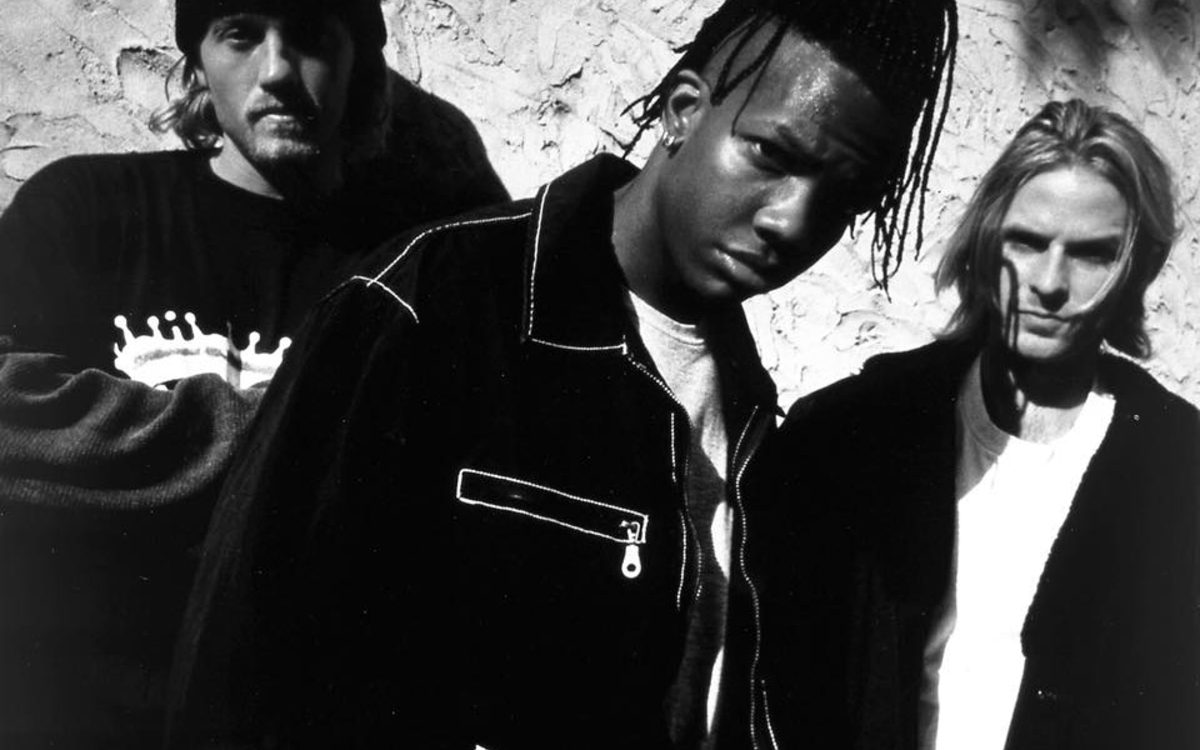

Comprised of three guys who met while attending Liberty University, dc Talk might be the most influential act in CCM history (outside of Amy Grant). And while I still contend that Free at Last is the group’s best and most cohesive musical statement, Jesus Freak might have the longest-lasting impact.

Already on top of the CCM world because of their personal charisma and a pop style of hip-hop that didn’t completely scare away the traditional (read: white and conservative) CCM fans, Toby “Mac” McKeehan, Michael Tait, and Kevin Max Smith released a 13-song album that wholeheartedly embraced the grunge style of alternative rock that had swept through secular music over the previous 4 years. And instead of scaring CCM anew, it drove their superstar status to incandescent heights, complete with the album charting on Billboard for the rest of 1995 and into 1996.

As a Christian kid in the ‘90s, Jesus Freak was definitive proof that Christian music could be cool, hip, and relevant – all while still showcasing a strong witness for Jesus through alternative rock music.

In writing about Jesus Freak for the vaunted 33 1/3 series, Dr. Will Stockton and Dr. D. Gilson looked back both fondly and critically upon an album they also count as transformative in their experience as Christians. As someone who has left behind evangelical Christian culture, I was curious to read how two professors of English and Cultural Studies would regard this record. Or, to borrow from the back cover of the book:

“Written by two queer scholars with evangelical pasts, Jesus Freak explores the importance of a multifarious album with complex ideas about race, sexuality, gender and politics.”

The book critically looks at the three standout songs of the album – the three songs that also had accompanying official videos: “Jesus Freak,” “Colored People,” and “Between You and Me.” While other tracks get their due when appropriate, including “So Help Me God,” “What If I Stumble,” “Like It, Love It, Need It,” and “What Have We Become?,” our authors were correct in placing their focus on those three big tunes.

“Jesus Freak” serves as the touchpoint for discussing how dc Talk interacted with culture, specifically ‘90s alternative rock culture. The book provides a brief, if authoritative, explanation of that entire scene, paying specific attention to how many of the bands and singers of that era rejected the trappings, message, and teachings of Moral Majority Christianity. By recapping various interviews given by dc Talk and placing them alongside the song’s lyrics, Stockton showcases how the trio saw themselves as casting a light into the darkness.

The book made it obvious that dc Talk wasn’t worried about accusations of being musical copycats.

They were more interested in making popular music that contained a Christian response to the nihilism of ‘90s alternative rock acts like Nirvana, Nine Inch Nails, and Smashing Pumpkins. Moreover, Stockton directly addressed how dc Talk overtly sought to take back the noun “Freak” from popular culture and apply it to how Christians should really live out their lives. In fact, Stockton claimed that dc Talk was purposeful in how it wanted to relight the flame of the ‘60s Jesus People movement into ‘90s CCM, a statement I found to be quite believable.

With “Colored People,” Gilson recounted his various personal experiences singing this song with his all-white youth group in a host of circumstances, including a mission trip to inner-city Detroit. But instead of completely lambasting the lyrics as hopelessly out-of-touch and downright offensive in a 21st century context, our author introduced both context and nuance to the discussion.

He first explained the nature of ‘90s neoliberal multiculturalism, wherein the concept of “color blindness” took hold both in popular culture and the Christian church. He then talked through how despite a chorus that claimed that “we are all colored people,” much of the verse content showed dc Talk willingly addressing the terrible racism inherent in much of Western – and definitely American – Christendom. From there, Gilson also discussed a century’s worth of musical appropriation wherein white artists have at best borrowed and at worst stolen from black musicians, whether it’s been Elvis, Vanilla Ice, Macklemore, or Toby Mac.

Thus, while not letting a trio comprised of two white guys and a black guy off the hook for a now-cringeworthy song about the possibility of a “Color-blind Utopia,” the author gave credit to dc Talk for its attempt to stand in the prophetic tradition of Martin Luther King, Jr., Cornel West, and others by using its platform to help Christianity face up to its racist past and become better.

Working together to examine “Between You and Me,” our two authors examined how the music of dc Talk directly impacted how they each explored their burgeoning adolescent sexuality and eventual coming out as gay men. The lenses utilized include the Biblical friendship of Jonathan and David, the Promise Keepers organization and its “emphasis on domestic heterosexuality,” the college friendship of Toby and Michael, and the song’s use of “you” to possibly mean more than a conversation between the singer and God.

Starting with a 2011 interview in which Toby and Michael talked about how the two pushed together their beds in college to form one large bed, Stockton and Gilson “reminisce[d], albeit analytically, about our evangelical adolescence and the queer relationships we had with boys and the God who united us.” Not only was this chapter remarkably personal and intimate chapter, but it contained a fresh and interesting take on the use of “you” in CCM.

Using a concept called “girlish masculinity” (initially coined by Gayle Wald in 2002), they talk about how boy bands through time immemorial have appealed to both heterosexual girls and homosexual boys because both groups can envision themselves as the “you” to whom the singers croon.

For both authors, “Between You and Me” served as a prime example of how the “you” could have multiple meanings, depending upon the listener. It came complete with a claim that it revealed how dc Talk often treated each other (however subconsciously) as spouses. And when taken in conjunction with how they broke down the staging and framing of the video for this song, it’s a claim with some weight.

Jesus Freak remains one of the classics of CCM I revisit on a semi-regular basis, even if it’s just so my wife and I can quote the lyrics back-and-forth to each other on long car rides.

I also credit the blurred genres on display with this album as a foundational text for my slow-burning acceptable of poptimism. In short, it will always be with me, even as my personal beliefs and expressions of religious faith have changed dramatically since 1995.

And for all of the changes that have occurred in their own lives since the release of Jesus Freak, it seems that Will Stockton and D. Gilson have much the same feelings about this album. At least that’s what I take away from this excellent book – that and the desire to chat with these two about ‘90s CCM over a few drinks.