In the early 90s, the video game war was in full swing. Nintendo may have ruled the 8-bit era with the NES but Sega would prove itself as a formidable foe during the 16-Bit years. Nintendo took gameplay seriously and their games spoke for themselves. But Sega utilized edgier marketing to appeal to the older demographic. With high-tops and a smug look of confidence, Sega’s mascot Sonic The Hedgehog played against Mario’s hopeful innocence. It was just cooler to be team Sega. Well, for anyone under the age of 13 anyway.

Part of what made Sega so appealing was celebrity endorsement. Early in the Genesis life, Sega teamed up with Michael Jackson for a video game version of his Moonwalker film. While not a good game by today’s standards, its pretty wild to play as Jackson in a side-scrolling adventure attacking mobsters with dance moves. The absurdity of such scenario has kept the Moonwalker film a pop culture treasure and the video game adaption a cult classic.

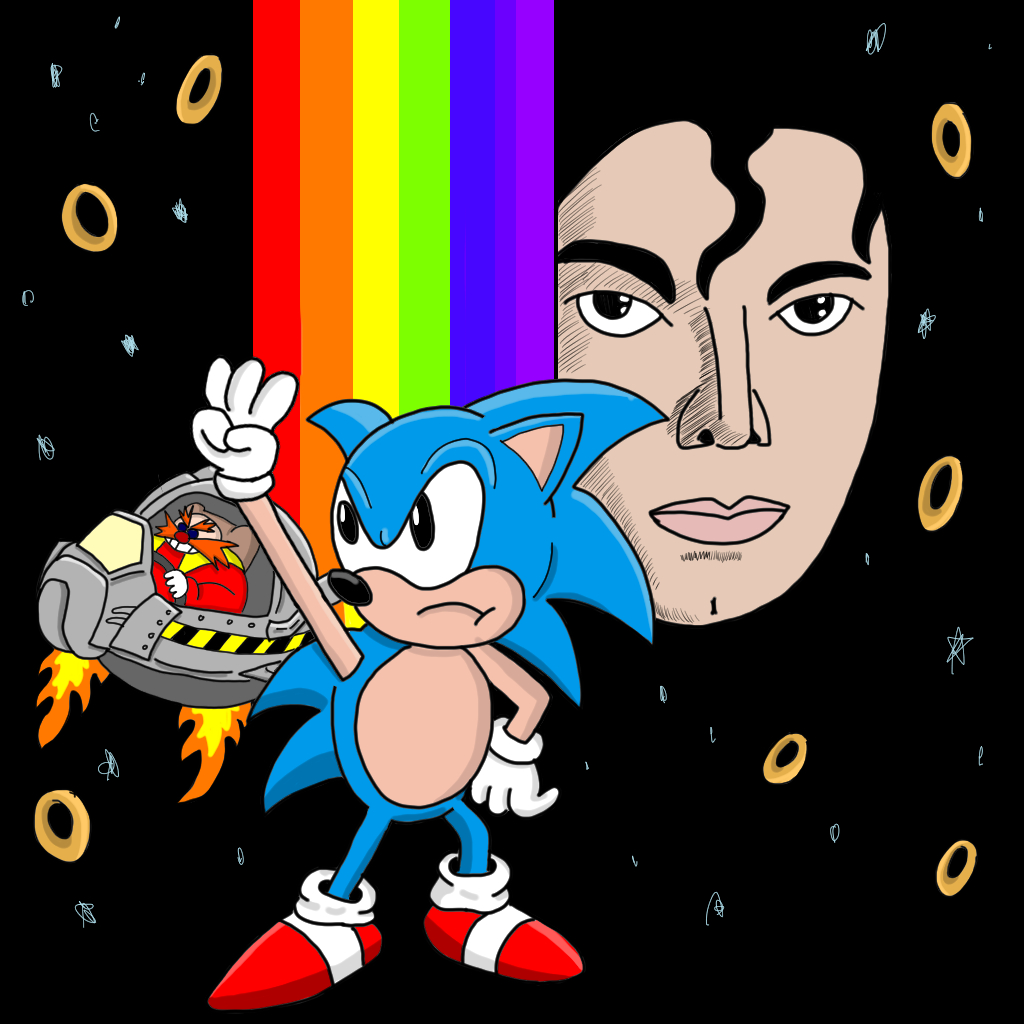

But it would be the combination of Jackson and another Sega franchise that would become one of the most interesting conspiracies in gaming history.

Soon after the release of Sonic The Hedgehog 3 in 1994, players began noticing similarities between the game’s music and the works of Michael Jackson. For the next two decades, bits and pieces of information surfaced regarding Jackson’s rumored involvement with the game. But it wasn’t until nearly ten years after Sonic 3‘s release the cat was out of the bag. Thanks to an early YouTube video pointing out similarities between the game’s music and Jackson’s, the ball began to roll.

The first official confirmation came from Roger Hector, the former Sega technical director. In a YouTube video, Hector confirmed Jackson was in fact linked to do the music of the game early on. In the same interview, he claims involvement was scrapped due to Jackson’s infamous misconduct allegations in 1993. But what about the songs in the game that sound like Jackson?

When pressed for details on what Jackson completed, Hector said in-house composer, Howard Drossin was brought in to complete the game’s music upon Jackson’s exit.

It’s worth noting the production of Sonic 3 started loose and improvisational. Developers were encouraged to go wild with ideas despite the hardware’s limitations. But pressure to have a Sonic game ready for the holiday season forced developers to work faster than expected. To alleviate the pressure, Sega built Sonic Spinball from the ground up in just under 5 months to meet the deadline. Drossin’s ability to compose a soundtrack in such little time made him the go-to for Jackson’s exit.

To buy even more time, Sega decided to split Sonic 3 into two parts. The second part eventually became what we know as Sonic & Knuckles. If you’ve played both games you would know the soundtrack to Sonic & Knuckles is vastly different than Sonic 3’s. Where Sonic 3’s music is more groove and New Jack Swing influenced, Sonic & Knuckles goes back to a traditional score closer to previous installments.

This lends itself to the theory of Drossin composing most of Sonic & Knuckles’ and the majority of Sonic 3 the result of Jackson and his crew.

In 2009, French magazine Black Or White gave fans some insight by publishing an interview with Brad Buxer. Not only one of Sonic 3’s lead composers, Buxer worked as Jackson’s music director for years as well as being one of his closest friends throughout the 1990s.

Buxor admits he has yet to play the game but confirms he did write music for the project. He also goes on to say the end credits theme was the basis for 1996 single “Stranger In Moscow”. More interesting is the fact Buxer directly contradicts Hector’s claim of Jackson’s music being scrapped. Stating if Jackson isn’t credited as a composer, it’s because he was disappointed in the sound quality of the system. Jackson reportedly didn’t want to sign off on something that devalued his music. Adding to this development is the timeline. According to Jackson’s touring schedule, he backed out of Sonic 3 months before the allegations surfaced.

Despite writing some of the greatest pop songs of all time, Jackson couldn’t play an instrument.

Both Buxer and fellow Sonic 3 composer Cirocco Jones said Michael would sing melodies and ask them to play it back with instruments. Jones once stated in an interview he still has the tapes of Jackson singing the entire soundtrack to the game. Can you imagine what a trip it would be to hear such recordings?

Jackson was also notorious for being a perfectionist. It’s very possible Jackson wasn’t happy with the quality. But maybe Sega took the opportunity to back out as well? Jackson dragging his feet wouldn’t be doing the company any favors, especially with the given time limit. With so much speculation on this subject, it’s virtually impossible to decipher what exactly happened or how much (if any) of Jackson’s contributions made it to the final release of Sonic 3. Listening and drawing your own conclusions is the only option. Fortunately, that’s the easy part. Sonic 3′s soundtrack is easily the best of the 16-bit era. From rock, new wave, and dance, the music is just as diverse as the game’s locations.

As discussed in a previous installment in this series, video game scores are generally driven by a leitmotif.

Without starting a lesson in music theory, a leitmotif is a musical gesture in a composition associated with the lead character. The best example of this is the opening bars of the Super Mario theme. By just hearing its first measure, you already know it’s all about Super Mario. With the first two Sonic The Hedgehog games, Sega hired Masato Nakamura, the bassist and primary songwriter from the Japanese pop group Dreams Come True.

Nakamura’s background in pop music gave the Sonic team an advantage in creating a much cooler vibe for the character. The music in those games tossed out the leitmotif idea and replaced them with hooks found in pop music. When listening to those songs, the first thing you’ll notice there are no strong resolutions within its melodies. Instead, each chord passes back and forth with the ease of any good pop hook. Compositions of Sonic 1 & 2 are intentionally simple by design to match the aesthetics of the character and the levels. Sonic is in constant motion and the music reflects that.

With Sonic 3, there’s an obvious shift in composition.

The most interesting music cues expand upon Nakamura’s pop technique, resembling something you would hear on the radio.

For example, “Hydrocity Zone” is over a minute in length as opposed to the tracks featured in previous games being around 20 to 30 seconds. Just like a legitimate pop song, there’s a verse, chorus, and a bridge. If the average playthrough of the level is 3 minutes, the player will have only heard the song 3 times. When comparing the music to previous installments, Sonic 3 is definitely far more theatrical. At this point in his career, Jackson was already creating music with cinematic flair.

Another important song in Sonic 3 is the music in Ice Cap Zone. On the surface, the bass line is similar to Jackson’s “Who Is It”. But upon further investigation, Ice Cap Zone was originally a demo called “Hard Times” from Buxer’s previous band The Jetzons. This finding pretty much obliterates Hector’s claim of Howard Drossin doing all the music in the game. Even after Jackson’s exit, the remaining composers probably stuck to Jackson’s groundwork. Not only because it was easier, but maybe even for the sake of consistency?

The Jackson-isms don’t stop there.

Some of the compositions find their way into Jackson’s music after the release of the game.

Knuckles Theme is made up entirely of beatboxing and sounds exactly like the beat in the chorus of Jackson’s “Blood On The Dance Floor”. Essentially the theme for Carnival Night Zone is an alternate arrangement of “Jam”. All the way down to the sample of Heavy D saying the song’s title. On the topic of samples, Sonic 3 uses quite a few audio samples in it’s music from drums to what sounds like Jackson’s signature woo’s and come on’s. Unfortunately, the muffled beats and distorted samples prove sound quality wasn’t the strong suit of the Genesis. It’s easy to understand Jackson’s frustration. Especially when taking into account his perfectionism.

Poor sound quality is the result of compressing large files into the cartridge. I’m not experienced in game design, but there had to be a reason why Sonic 3 was split into 2 separate games in the first place. Perhaps Sega was trying to conserve space to fit Jackson’s music and had no choice but to split it? After all, the music in Sonic & Knuckles is far more simple in design. Without huge audio files taking up space, the developers had room to adjust for the ‘lock-on’ technology featured in the game. Surely a gimmick letting players play as Knuckles in previous installments would need more space than a few digitized songs.

The most disheartening thing about this discussion is how we’ll probably never to get a straight answer to our questions.

Despite Sonic 3 and Sonic & Knuckles being highly successful games for Sega, it marked the end of an era. As the 90s came to a close, Sega tightened up and took a colder, corporate approach to their creativity. Sadly, it didn’t work out too well and Sega dropped out of the console market just a few years later.

Just the idea of an artist reaching across genres and mediums seems like an anomaly. Whether Jackson’s music remains in the game or not, he clearly had a heavy influence on the finished product. The fact we’re still theorizing the details over two decades later is a testament to how interesting the correlation is. It isn’t likely we’ll ever get to the bottom of this mystery. But it’s cool to think there was a time these media juggernauts teamed up to give us something timeless as Sonic The Hedgehog 3. Controversies and all.