The news was of course, unbelievable. Prince dead at 57. How could it happen? He’d stopped a tour and visited a hospital because he was sick, sure, but it was only the flu. People get the flu every year and they’re okay? It seemed like a cruel twist of fate. But people forget: the flu is deadly. About a century ago, the flu killed more people in one year than a World War did in four. People forget.

We forget a lot of things. We forget what we ate the day before, we forget the name of the person serving us our coffee in the morning and we forget what record we listened to in the evening the day before. But Prince, how do we remember him? A killer guitar player? A musical prodigy? A visionary on how to control your back catalogue? As someone who re-defined what a man could look like and say on stage?

Now, people never exactly forgot about Prince.

He was a steady touring act, playing live shows right up until a week ago. He kept a steady pace, releasing records all the time. He released one last fall, HITNRUN Phase One. He released another late last year, Phase Two. You’ll be forgiven if you missed either; they didn’t exactly tear up the charts. But both are great, showing him and his backing band 3rd Eye Girl, in top form: funky, tight and hard-rocking. Right up until the end, he was in top form.

It was a remarkable run for the Purple One. He started as a young prodigy, making music himself in the studio. Early on, the Village Voice’s Robert Christgau called him a studio rat and the label made sense: Prince wrote and produced his own music, playing everything himself. In 1978, he released For You, a good record but not one that tore up the charts. That said, the slick funk of “Soft and Wet” showed that even at 19, Prince knew what sound he was going for and how to get it.

Over the next 16 years, he had one of the most prolific runs of anyone in music had during the 20th century. Almost everything he made between 1979 and 1995 is essential and even the lesser albums are great and worth anybody’s time. Records like Purple Rain, Around the World in a Day, Sign O’ the Times, and Dirty Mind are mainstays of anyone’s best-of lists. At the same time, records like Lovesexy, Controversy, and Diamonds and Pearls are as good as anything anybody else was making. His bands were top notch: The Revolution, The New Power Generation, and Madhouse, backing musicians like Shelia E., Wendy and Lisa, and Dr. Fink.

What makes this streak so incredible isn’t what he released, but what he didn’t. A cursory glance through the 80s pop charts shows many songs Prince wrote and gave to other artists without releasing himself: The Bangles “Manic Monday,” The Family’s “The Screams of Passion,” Shelia E’s “The Glamorous Life,” Vanity 6’s “Nasty Girl,” Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2U” and Morris Day and the Times’ “Jungle Love.” There are others as well.

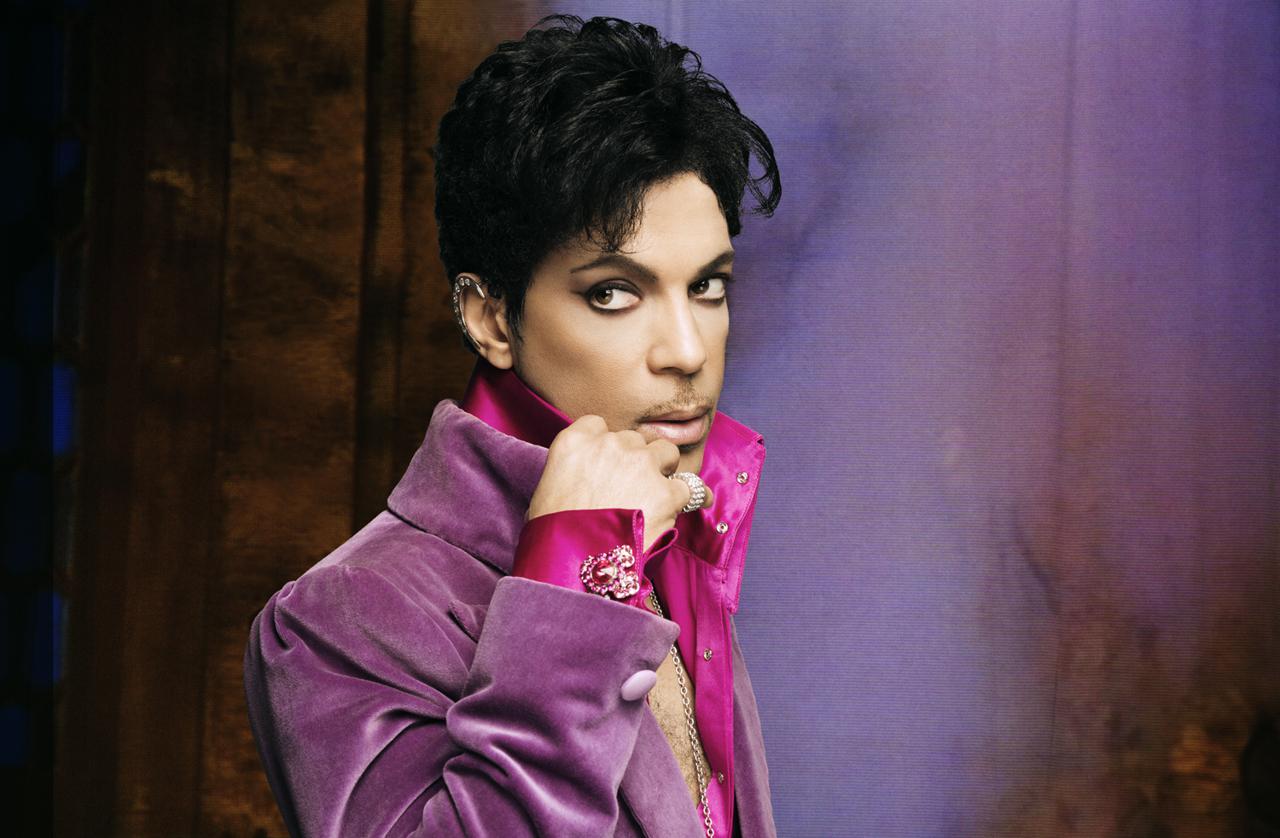

Never one to shy away from controversy, Prince’s career was packed to brim with ways he was transgressive in ways other than his music. Take the way he dressed: his ruffled coats and slinky underwear, he was decidedly out-of-step with his peers in music, presenting an alternative to over-the-top machismo. Over the course of his career, he presented himself like this, wearing heeled boots, touches of makeup and an elaborate hairdo; at the same time, it always seemed genuine, not like he was wearing a costume for his public image.

Of course, there are other ways he pushed the boundaries for what artists can do. He was both an early adopter of the internet – he released a record through his website in the 90s – and one of it’s fiercest critics. He fought to keep his music from getting pirated with a zeal only matched by Robert Fripp and Bob Dylan; like them, he even kept his music off YouTube for eons. Unlike them, it’s hard to find it even now. He didn’t like streaming – except for Tidal, which he said paid him a fair rate – and owned the masters to his records.

Which, as I’ve examined before, is the most important part of his legacy. As someone with a large and popular discography, Prince handled his back pages with masterful ease. He kept his records in print, but only in their original form. He would issue music in new and interesting ways that kept fans on their toes: it could be over the internet, included with a newspaper, or only available in small batches through his fan club. There are no deluxe issues for any of his records, but there are singles upon singles, 12” records and EPs, CD-Singles and cassettes for everything. More than anyone else, he controlled the message and kept his fans wanting more; at the same time, it showed how a canny, intelligent musician was able to thrive in a marketplace making it hard for them to keep afloat.

You could never have enough Prince: the more you look, the more you find. For example, a digging trip could result in the 20-minute extended version of “America,” originally a nervous, taught number about patriotism on Around the World, but a lengthy, exciting jam on the 12” single. Just about every one of his records held surprises like this.

Of course, his records each have surprises when you dig into them. People often focus on his 80s heyday, but throughout his career, his music was engaging and exciting. For example, 1995’s The Gold Experience showed his music taking a hard, driving energy and his guitar rocking with a sludgy energy (listen to it roar on “Endorphinmachine”), while 2006’s 3121 had him reclaiming his R&B roots with gusto (dig “Love”). Even his jazzier records had moments where everything clicked and showed his relentless drive to make music and push everyone’s boundaries, even his own. Who else crossed boundaries – in music, ownership, and expression – like Prince did?

Even last year, Prince was sharp, active and funky. On Hitnrun Phase Two, he opened the record with a sizzling slice of 70s soul funk addressing racial unrest, police violence and the death of Freddie Grey with élan, expressing frustration, anger and, ultimately, love: “We’re trying of crying and people dying, let’s take all the guns away,” he sings, “enough is enough, it’s time for love, it’s time to hear the guitar play.” As the strings build, the backup singers say Baltimore over and over, his guitar darts back and forth until a choir of voices emerges, chanting “If there ain’t no justice, than there ain’t no peace.” Sure, it’s not the equal of Kendrick’s “Alright,” but it’s message is a hell of a lot more pointed than almost anyone dared release, too.

Which, maybe, is the best way to remember the guy. He took a lot of unpopular stances in his career and courted anger and outrage – his song “Darling Nikki” inspired the PMRC hearings that led to those warning labels on records – but he also never stopped making music, chasing his muse and keeping fans in the hunt after him. Prince Rogers Nelson will be missed, but he’ll always be searched for and discovered, year after year, decade after decade.