Back in the stone age of music, if you weren’t there for a live concert there was no real way to know what happened. Even now, there’s still apocryphal stories from these days: did Frank Zappa really take a shit on stage? Did Jerry Garcia really fall to his knees and get back up while playing a solo? Did Iggy Pop really smear peanut butter and broken glass all over his chest and roll around?

We have a pretty good idea – in order, no, probably not and almost certainly – but we don’t really have any definite proof, just word of mouth. People tell their friends about this great show they just saw, and can’t you believe it, the most unbelievable thing happened! Their friends tell other friends, who tell their friends. The story spreads and amplifies as it’s removed from the source. Soon, it’s like Rashomon: we know there’s a dead samurai in the woods, but we’ve got four stories of how it went down and none of them agree with each other.

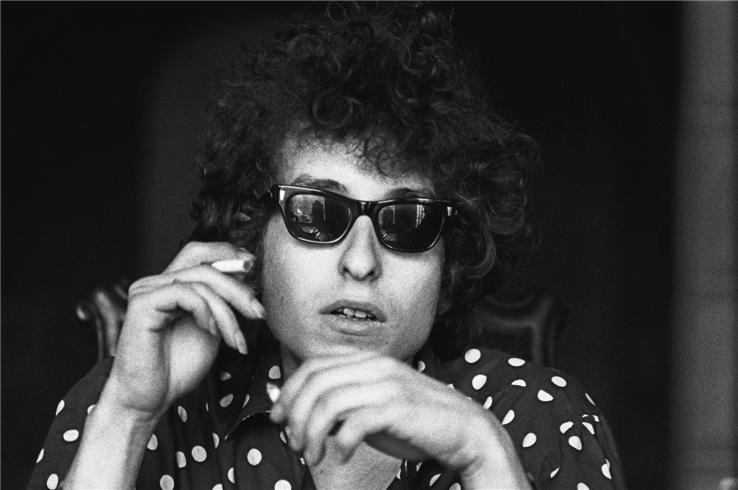

One of the most famous stories involves Bob Dylan. Before his self-imposed exile in 1966, Dylan went through a handful of changes. Now, they’re looked back on as a creative evolution, but at the time each attracted controversy. When Dylan started writing more personal songs and moved away from traditional protest ballads, he’d succumbed to self-indulgence. Soon he was playing with an electric backing band; the haters said he was selling out. At the Newport Folk Festival, he played a loud, brash take of “Maggie’s Farm” as organizers ran around backstage and tried to cut his amplifiers off. It was a crazy time, only getting crazier as it went on.

One of the most famous stories involves Bob Dylan. Before his self-imposed exile in 1966, Dylan went through a handful of changes. Now, they’re looked back on as a creative evolution, but at the time each attracted controversy. When Dylan started writing more personal songs and moved away from traditional protest ballads, he’d succumbed to self-indulgence. Soon he was playing with an electric backing band; the haters said he was selling out. At the Newport Folk Festival, he played a loud, brash take of “Maggie’s Farm” as organizers ran around backstage and tried to cut his amplifiers off. It was a crazy time, only getting crazier as it went on.

He’d been working hard on several projects that year: a book and an album while crossing the country on tour. Days between gigs were for dropping into the studio to bang out a couple takes. By the time he got to England, filmmaker DA Pennebaker followed him to capture a documentary. Dylan fielded questions from ill-prepared reporters (sample question: “Would you say you care about people?”) and hostile crowds who booed, threw bottles, and walked out on his sets. Finally, on a Tuesday night in Manchester, things came to a head, climaxing with Dylan verbally jousting with a heckler. Small wonder it entered bootleg lore (although people usually got the location wrong, hence the “Royal Albert Hall” title”). Small wonder it was the first full concert Dylan released on his long-running Bootleg Series of CDs.

At the time, Dylan’s shows were split into two sets. First came an acoustic set, just Dylan and his guitar (and occasionally harmonica). On this night, he’d play several of his newer songs – “Desolation Row,” “Visions of Johanna,” “4th Time Around” – and while they’re not astounding performances, they’re fun versions of some of his best material. These stripped-down performances are much more barebones than the album versions, sparse and intimate: there isn’t the layer of separation you get from an amplified band or a layer of studio polish. Not to mention a skeptical crowd. And as he goes on, his playing perks up (especially on “It’s All Over Now,” “Baby Blue”) – did he win them over? Or was he just happy to get the preliminaries out-of-the-way? The applause he gets only builds the anticipation knowing what’s to follow.

His second set, despite all the hype and stories, completely delivers: it’s one of the best live albums of any artist, ever. Dylan and his backing band weave a jangling, bluesy sound as they rip through his songbook to an audience that’s by and large pissed off. On “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met),” Dylan and Co. turn his acoustic number into a stomper, a giving it a pulsing energy. Here, Dylan’s backed up by what is more or less evolved into The Band: Rick Danko on bass, guitarist Robbie Robertson, Garth Hudson and Richard Manuel on organ and piano. and Drummer Mickey Jones filled in for Levon Helms, who quit some weeks before. By the time of this show, they’d gelled into a cohesive unit.

The twin guitars of Dylan and Robertson give Dylan’s music an electricity it’d never had before, even on the studio albums. Nowhere is this more apparent than on “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” when Robertson’s guitar plays the piano line and the band crashes in behind him. Dylan, sounding rawer than his first yet set, yelling to be heard over his band and stretches out, sounding like the world-weary character in the song. Near the end of every verse, the band sounds set to explode, but Dylan keeps them in check. When he steps back and lets Robertson solo, the band kicks into gear and rocks out.

The twin guitars of Dylan and Robertson give Dylan’s music an electricity it’d never had before, even on the studio albums. Nowhere is this more apparent than on “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” when Robertson’s guitar plays the piano line and the band crashes in behind him. Dylan, sounding rawer than his first yet set, yelling to be heard over his band and stretches out, sounding like the world-weary character in the song. Near the end of every verse, the band sounds set to explode, but Dylan keeps them in check. When he steps back and lets Robertson solo, the band kicks into gear and rocks out.

This band has more muscle than anything Dylan had before. They were road-tested, having not only played with Dylan through some of his toughest crowds, but also playing for Ronnie Hawkins and on their own as The Hawks. On this tour, they brought their own amps and PA because no halls had systems powerful enough for them. They blast the music at the audience, giving Dylan’s music a kick lacking on albums like Highway 61 Revisited or Blonde on Blonde. It’d been a rough gig: jeers, people clapping off-beat, people yelling over his between-song banter, the occasional walk out. Him and his band took the crowd’s hostility and threw it back at them.

In a yell immortalized on bootlegs, movies and music lore, an upset Dylan fan screams “JUDAS!!!” during a pause. Another person accusing Dylan of selling out, of betraying his roots and fans. The crowd applauds the jeer with more enthusiasm than they’d showed Dylan’s electric set. “I don’t believe you,” replies Dylan, jangling his guitar. “You’re a liar!” He turns to the band, away from the mic: “Play it fuckin’ loud.” They crash into a bombastic, frantic version of “Like A Rolling Stone.”

In a yell immortalized on bootlegs, movies and music lore, an upset Dylan fan screams “JUDAS!!!” during a pause. Another person accusing Dylan of selling out, of betraying his roots and fans. The crowd applauds the jeer with more enthusiasm than they’d showed Dylan’s electric set. “I don’t believe you,” replies Dylan, jangling his guitar. “You’re a liar!” He turns to the band, away from the mic: “Play it fuckin’ loud.” They crash into a bombastic, frantic version of “Like A Rolling Stone.”

It’s one of his finest hours: he yelps and moans, stretching his voice nearly to the breaking point. The band pounds each bar of the music out, playing Dylan’s best song with a sense of urgency. If you didn’t know better, you’d think they were making a personal statement to the haters. It’s not any louder – to us, the home listener – but you can hear the rise in energy, the constant pounding of Jones, the intertwining guitars of Dylan and Robertson (who rips off licks like it’s nobody’s business) and the steady backing of Manuel and Hudson slowly builds up the tension until a final smash some seven minutes in. The music hangs for a second, Dylan says “Thank you” and that’s it. No encore, nothing. Just a few moments of silence before the recording fades out.

Just a couple of months after this show, Dylan crashed his motorcycle in upstate New York. He’d retreat from the spotlight, record some demos with The Band, then head to Nashville to record the acoustic John Wesley Harding. He didn’t tour again until 1974 – again, with The Band in tow.

Later this year, Columbia Records is releasing volume 11 of Bob Dylan’s long-running Bootleg Series: a six-CD set of those demos he recorded with The Band. It’s probably the most anticipated Dylan release in a while; these are the demos that formed part of the original bootleg LP Great White Wonder.

But until those come out, go back to Dylan at his fiery, powerful best. The “Royal Albert Hall” concert is one of the few living up to its legend. Listen and get a sense of why so many people went to great lengths to look for the Bob Dylan they remembered, going as far as pressing the bootleg to their own records.