I’ve never been to The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but I hear it’s nice: there’s lots of parking, it’s not too out-of-the-way in Cleveland and there’s a bunch of exhibits. As I understand it, it’s pretty much what you’d think it is: a shrine to music made by and for baby boomers, largely between the years of 1960 and 1980.

Of course, it’s more than that. In recent years, the Hall’s opened its doors to artists as diverse as Miles Davis, The Dave Clark Five, and both Buddy Holly’s and Bill Haley’s backing bands. Last year saw Randy Newman and Public Enemy were playing the same bill – which makes a lot more sense than I bet most people would realize – along with, for some reason, Rush. I guess the Canuck trio had to get in sooner or later.

On the whole, it’s a pretty white museum, which I suppose you’d expect from something daring to call itself the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. To its credit, it’s made strides in embracing both blues and hip-hop artists, but for me, race hangs over this year’s inductees in a way I haven’t really seen anyone embrace.

A little back story: for years, South Africa was subject to a culture boycott by the UN. This was because of a government policy on apartheid, a policy to institutionalize racism and segregation. Because of the stigma of supporting an openly racist government, few artists ventured there; Gram Parsons famously quit The Byrds rather than play there in 1968.

Enter Sun City: a state-owned casino in South Africa. According to a 1985 Chicago Tribute report, this casino used to offer huge sums of money to lure performers past the UN boycott. Sometimes it didn’t work, but only sometimes. One person it managed to lure was Linda Ronstadt, who (again according to the Tribute’s report), was paid half a million dollars to play six concerts there.

Enter Sun City: a state-owned casino in South Africa. According to a 1985 Chicago Tribute report, this casino used to offer huge sums of money to lure performers past the UN boycott. Sometimes it didn’t work, but only sometimes. One person it managed to lure was Linda Ronstadt, who (again according to the Tribute’s report), was paid half a million dollars to play six concerts there.

This helped turn popular opinion against Ronstadt, who defended her decision to cash in with stale lines like “the arts is no place for a boycott.” Music critic Robert Christgau threw her under the bus for this self-serving stance: “I stopped paying this stiff-necked middlebrow art singer much mind, which … was no great sacrifice.” So did Rolling Stone‘s Aaron Latham, who let her hang herself with her own words.

Over the years since, Ronstadt hasn’t done too much of note. She released a series of forgettable albums before officially retiring a few years back. Generally people have forgotten about her Sun City gig and hypocrisy, instead focusing on her influential early years or on how she can no longer sing due to Parkinson’s.

And while I’m no fan of hers, I can see why she was inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: in some corners, she’s seen as an important role in the evolution of country music. What fascinates me about her Hall of Fame induction is the timing: on the same day she was inducted, so was Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band. And there was no more vocal opponent of such gigs as the E Street Band’s lead guitarist, Steve Van Zandt.

Back in the day, Van Zandt didn’t just oppose apartheid; he spearheaded opposition to it, forming Artists United Against Apartheid. When Paul Simon went to South Africa, Van Zandt told the pop idol how wrong and pig-headed his stance was. (For the whole story, please read his amazing interview with Dave Marsh!) Having such a vocal supporter of civil rights getting enshrined on the same day as someone who claimed she was above them is fascinating stuff.

But sometimes I wonder what goes through the minds of the people in charge there at the museum. This year, for example, they inducted KISS, a cartoon-rock band that basically acted like they stepped out of the pages of something published by Marvel Comics in 1975.

This is not to slam KISS, mind you: I like some of their music and I like some of it quite a lot. They made a handful of good albums and perhaps more than anyone else, figured out that Rock Stardom is a business at heart and leveraged their brand into huge sums of money. Cynical, perhaps, but I can’t help but admire it, too. Plenty of musicians have gone broke over the years and not just older ones, either, as New York Magazine showed a while back.

This is not to slam KISS, mind you: I like some of their music and I like some of it quite a lot. They made a handful of good albums and perhaps more than anyone else, figured out that Rock Stardom is a business at heart and leveraged their brand into huge sums of money. Cynical, perhaps, but I can’t help but admire it, too. Plenty of musicians have gone broke over the years and not just older ones, either, as New York Magazine showed a while back.

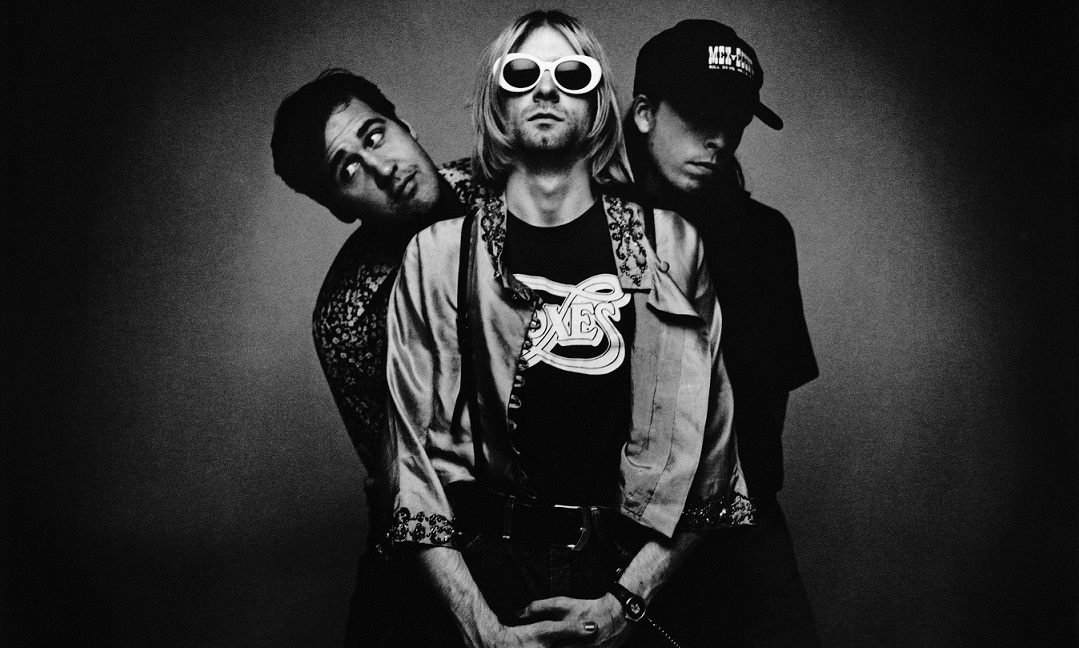

KISS was inducted on the same night as Nirvana, a band nearly as comic book-ish in a diametrically opposite way: if KISS is a over-the-top 70s comic (Superman takes on Muhammad Ali, perhaps), Nirvana is an early 90s anti-hero book, all dark and gritty. There’d be a lot of rain in their comic book, too.

And like KISS, Nirvana was an important band: they broke alternative rock, pushed the 80s college radio scene into the limelight and made rock matter in a way it hadn’t since, well, KISS’ live record. Kurt Cobain probably would disagree with me on that, I’m sure, but Nirvana rocked as hard as anyone. While some of their grunge peers released more music, Cobain’s music best reverberates in a way theirs doesn’t. Just about every sullen teenager owns a copy of Nevermind and most of them own In Utero, too. Cobain mattered in a way I can’t explain; listening to “Sliver” takes me back to when I was still in high school.

And like KISS, Nirvana was an important band: they broke alternative rock, pushed the 80s college radio scene into the limelight and made rock matter in a way it hadn’t since, well, KISS’ live record. Kurt Cobain probably would disagree with me on that, I’m sure, but Nirvana rocked as hard as anyone. While some of their grunge peers released more music, Cobain’s music best reverberates in a way theirs doesn’t. Just about every sullen teenager owns a copy of Nevermind and most of them own In Utero, too. Cobain mattered in a way I can’t explain; listening to “Sliver” takes me back to when I was still in high school.

Which, I suppose is what rock is all about: feeling young. Everybody knows someone who says music was better when they were young. It doesn’t matter if they’re talking about Duke Ellington, The Beatles, or Run-DMC: it was better back then, better than this garbage on the radio now. And in 20 years, I’m sure I’ll hear people telling me music was better back when Beyoncé was still releasing albums.

Maybe the whole purpose of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is to support this feeling. To be a reassuring place where you can go and feel assured that yes, the best music was the stuff you listened to when you were young. While I think the results of their selections this year are fascinating in relation to each other, they stand out all the more when viewed in this context: the sullen teens who bought Nevermind are nearing middle age now, while Springsteen still plays three-hour concerts and releases albums of original (and timely) material. Country music has never appeared closer to the mainstream, mostly thanks to one crossover success.

And while Spider-Man may have died a few issues back, comic book heroes never really die. As Gene Simmons explained in Rolling Stone the other day, someone else will just come along and wear the face paint.

For more from M. Milner check out even more of his incrediblism.